Several weeks ago, intent on continuing my pattern of exploring retail locations rather than shopping online, determined to encounter people in the flesh rather than on Zoom, I wandered into a sex shop on Connecticut Avenue. This particular store is named after a biblical reference and can be accessed only through a long staircase to a mezzanine floor. Upon my entrance I was shocked by the presence of an unexpected creature sitting on the counter: a small, gleaming grey cat with green eyes. She sat beyond my reach, three feet behind the cash register. I am accustomed to seeing cats in musty old bookstores, but never guarding a row of collars, leather suspenders, and ball gags. I beckoned her to come closer, but she stared at me indifferently.

Her meditative gaze reminded me of a description of the way such animals look at people in Colette’s short novel “The Cat” (1933): “inhospitably but with no animosity.” It seemed fitting for such a creature to be the guardian of this specific demimonde. There was something knowing about her countenance, both wise and perverse, and she seemed perfectly content to perch there among the contraptions. Her refusal to come closer said something about the nature of eros itself and its maddening capacity to conjure chimeras.

I first encountered Colette, the great French author of novels such as “Chéri” (1920) and “Gigi” (1944), when I was fifteen and acting in a school play. I found her again in a class several years later. College was not for me, and I barely made it through. I dropped out once and took an additional leave of absence before finally graduating at a different place than the one I had started in. There were very few experiences of academe I wished to keep with me, but three courses made a permanent impression: the first was called Comparative Romanticisms, taught by Professor Richard Sieburth. Sieburth was a genius, illuminating Goethe, Chateaubriand, and Blake in a way I had never imagined possible (even having grown up with a Blake fanatic father). Still, I was a little shit, giggling in the back of the class with another girl and falling into paroxysms every time he said something like “everyone was drunk on Kant.”

Another class that made an impression was “Silk Sheets: Writing Erotica,” taught by a minuscule New York bohemian named Tsaurah Litzky. She, too, was brilliant, explaining that all eros is actually about love, noticing that I was a writer and helping me grow, and donning all manner of leopard print sheath dresses with bulky athletic sneakers. She lived in a loft with an unheated room which she offered me one fall when I was looking for housing (I didn’t take her up on it). Under her benevolent watch, we studied Sade, Pauline Réage, and Pat Califia, and read our creations aloud.

The third class that made an impression concerned the Belle Époque and was taught by an ancient man whose name I no longer remember, and who seemed so old as to have lived through the era himself. There, I finally read Colette, and since that year there has been no other writer to whom I have felt so close. Her life seemed parallel to mine, and I have always taken her as a model in a world which did not seem to offer desirable pathways for a woman of letters.

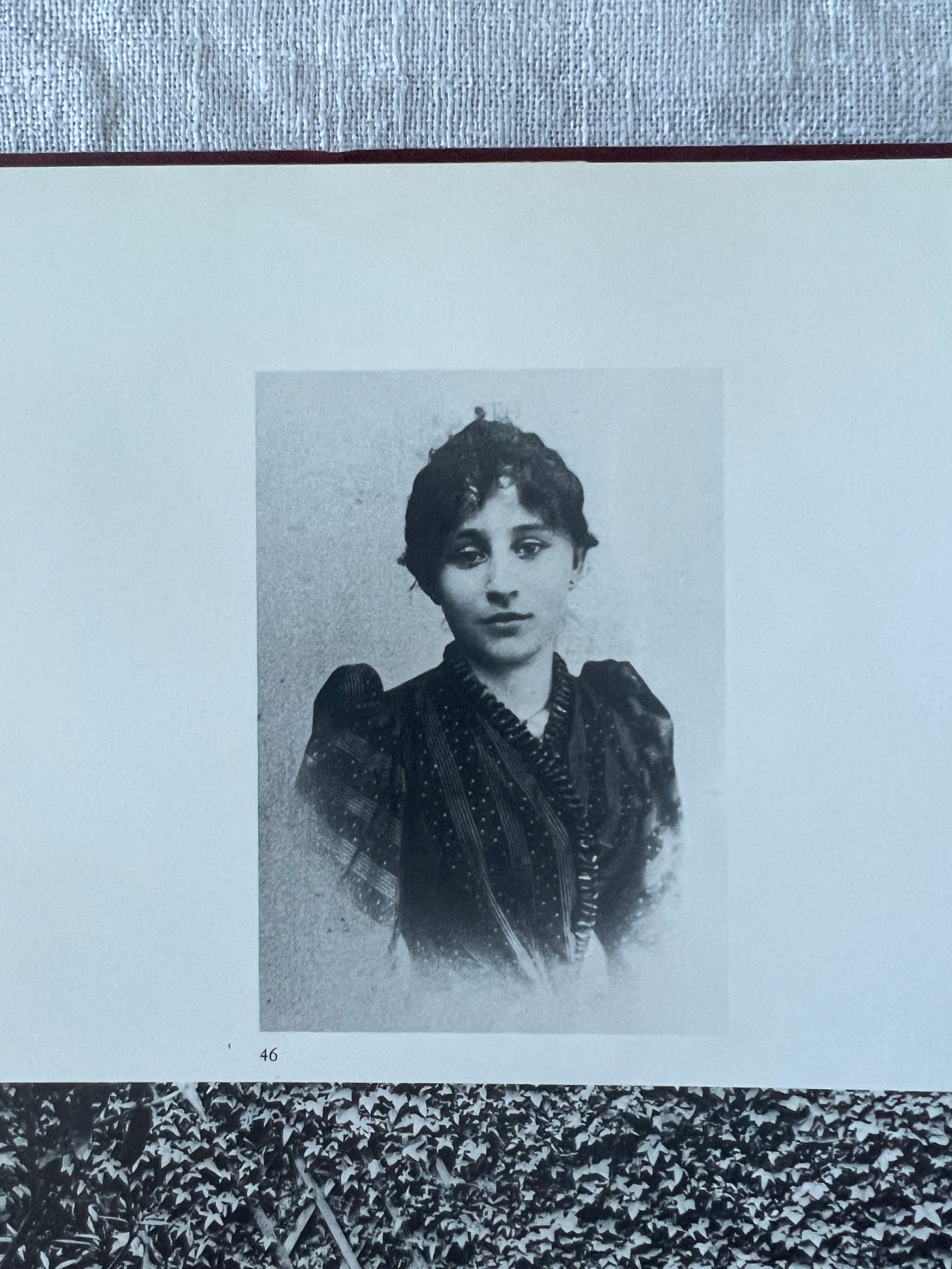

Sidonie Gabrielle Colette was born in central France in 1873, to a mother who was “at once traditional and eccentric,” according to biographer Geneviève Dormann. Her parents were very much in love, and the family lived in a country house with two gardens in a town called Saint-Sauveur-en-Puisaye. Madame Colette was enthralled with “her husband, her children, her animals, and her plants,” and was the sort of person “who would agree to wake her ten-year-old daughter at three in the morning so that she could see the summer sun rise over the countryside.” Allowed to roam in the fields nearby for hours in her youth, the author remained “provincial at heart” and retained a “violent peasant sensuality” as an adult woman: “even animals were mysteriously drawn to her.” Her mother would teach her to look but not to touch when viewing a delicate flower, and later in life she would create her own home “given over to old trees, wild roses, hazels, and free-ranging cats.” She was sexually voracious, and it was said of her by a leading critic that “her body has that awareness that plants, animals, children and women who do not curb their instincts never lose.”

The figure of Colette reminds me of country star Jason Aldean’s homage to rural femininity, “She’s Country,” from his 2009 album Wide Open. Aldean begins the song by asking his boys if they have ever met a woman of genuinely rural character: “ever met a real country girl? Talkin’ true blue, out in the woods, down home … from the song she plays to the prayer she prays … she ain’t afraid to stay country.” And neither was Colette. Even once she became famous, she was averse to stuffy high society settings. “Places where I cannot say merde make me ill,” she told a friend.

At the age of twenty she married the pompous yet charming literary entrepreneur Henry Gauthier-Villars, known as Willy. He was to encourage her to write, but also took credit for her first enormously popular compositions. When I say “encourage,” I mean “lock her in a room:” for that is precisely what Willy did, for four hours at a time. It was the only way she could get down to business. Colette was not naturally inclined to write, confessing in a letter that it was “disgusting work.” “I loathe writing,” she said, preferring instead a life of “bare feet, a faded bathing costume, an old jacket, lots of garlic and going swimming whenever I feel like it.” Although she became more prolific as she advanced in age, she insisted that “when I was young, I never, never wanted to write … Day by day, I realized more clearly that I was cut out not to be a writer.”

I remember moving in the middle of my childhood from a farming community in central New York to an academic town where one of my parents had found work at the library. One of the first things I noticed was how out of touch with their bodies the academics seemed: belts raised to their chests, shrunken, stooped-forward necks, and feeble laughs. They seemed a different species entirely from my grandmother, in whose house we pressed on pie crusts to make patterns with our thumbs. My distaste for esoteric jargon is deeply rooted in my earliest years. I could never get accustomed, after growing up with family who said words like “hogwash” and “hind end,” to people who used terms like “heteronormative.” I am not an academic and I do not make academic writing for academics. I like redneck rhetoric. I relate to the spirit of Colette, who once was approached by Marcel Proust (then a sensitive young literary man) at a dinner, and when he rhapsodized about how her writing was the “[daydream]” of a “soul …full of voluptuousness and bitterness,” she replied, “Monsieur, you are raving. My soul is full of red beans and bacon.”

She was indeed a glutton, and according to Dormann “was convinced that an empty stomach is an invitation to despair.” She told a female friend that physical pleasure was the antidote to mourning. She loved “raw artichokes and grilled almonds,” “a dessert sticky with natural sugar,” “cognac-flavored meringues filled with cream,” “salad with garlic twice a day” and “fresh onions the rest of the time,” “blackberry jam,” and “cherries in eau de vie.” On the return of a lover she corresponded with a friend that she was “letting [her]self enjoy an ephemeral, animal happiness.”

Colette was a popular author and she knew that her writing on sex and romance was the meat and potatoes of her calling. In addition to being a novelist, she was a journalist and contributed both reporting and columns to various publications. She was a working writer, not an intellectual. Finding her as a young female reader, I saw in her my same compulsion: to flee the life of the mind for the life of the senses. Her writing was for everyone. I wanted to read and write things that brought me pleasure — never in a million years would I have wanted to create something so arcane and dry as to make a regular person want to bang their head against a wall. For this is also what it means to be a populist.

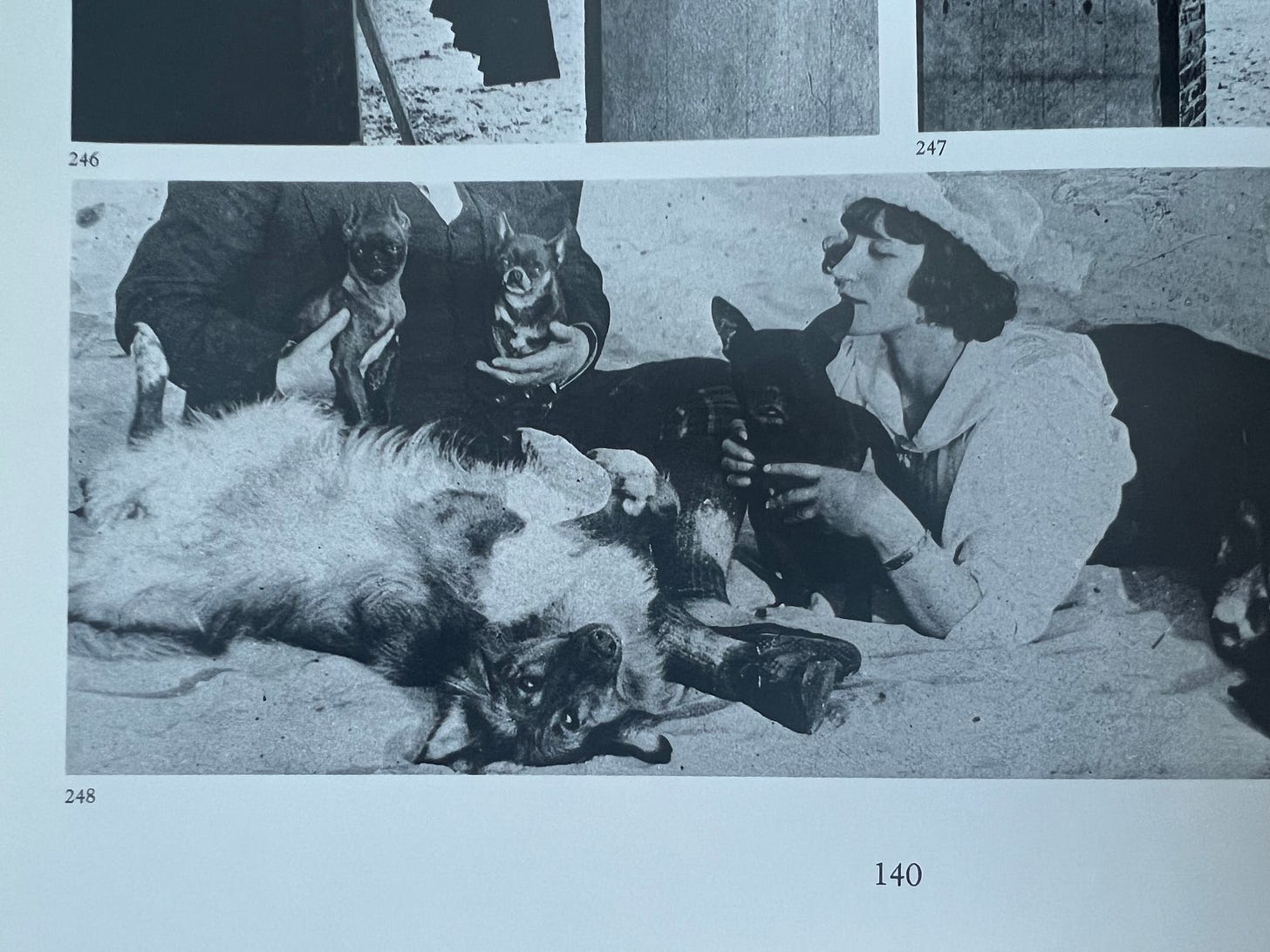

Colette’s oeuvre is about lust for “a fine head of lettuce, the supple back of a cat or a well-built man.” The author André Billy said that “Colette’s contribution” was to “[open] up the world of scent and touch … ideology … [is] alien to her.” What subjects consumed her? Things like “black figs that bleed white juice when you pluck them.” Instinct was everything. Colette remarked that she was not interested in death, not even her own. She was not a tragic woman writer or tedious doomed poet, of which there are so many. She was sturdy and of the earth. The essence of Colette is profoundly pro-life: pro-fertility, pro-food, pro-nature, pro-animals, pro-sex, and anti-suicide. Like a feline, she followed her desires and primal hungers. “We can hesitate a thousand times over the color of a dress,” she once said, “but for heaven’s sake we ought to be able to get married without thinking about it.”

The world of eros seems to frighten many people these days. There’s a sense that trust in impulse has been lost — men are afraid to pursue, and women are afraid to desire. Some people want to be neither men nor women. A “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” of today might have nothing to do with a wife who breaks out of a stultifying bond in order to find physical passion with a gamekeeper, but a young man who, trapped in airless cyber-existence, turns off the Internet and flees to the flesh and blood of a real woman. The dust jacket of my copy of “Chatterley” describes Mellors, Connie’s lover, as someone “who has not allowed this decadent civilization to destroy spontaneity in terms of naturalness of expression.” The realm of sex cannot be entered by the over-responsible. Thomas Moore, a former monastic, writes that “sex asks that we live joyously outside the perimeters of adult containment. We may feel soiled by the mess of this undisciplined world, which is sometimes that of the child, and yet it is healing.” This is not to suggest that children should be exposed to adult sexuality (they shouldn’t), but to remedy the stuntedness of adults who find themselves so monitored that they can’t connect.

The film “Poor Things” came out in 2023 and represents a return to the stylized cinema of titles like “Amélie.” Whereas “Amélie” told the story of a well-behaved neurotic struggling to overcome her introversion, “Poor Things” is about Bella Baxter, a raving, ravenous adult-bodied woman who has received a brain transplant from her own infant daughter. As we watch Bella grow into a woman in her thirties with a three-year-old mind, her demands, earnestness, and rapture at sensual experience are liberatory. She is perhaps the prelude to 2024’s cultural phenomenon, “Brat Summer:” the reclamation of joy and simple pleasure after a decade of paralyzing moralism.

Happiness consists in living traditional values in a relaxed way, not in living radical values in a perfectionistic way. This is something I learned while spending time in a monastery and speaking with an elder Catholic monk. During this period of my life, I acquainted myself with Saint Benedict’s sixth-century Rule: one of the first outlines for religious life, which is indeed full of regulations. It contains, however, the following sentence: “We read that monks should not drink wine at all, but since the monks of our day cannot be convinced of this, let us at least agree to drink moderately.” The Rule is a design for living for anyone who cherishes prayer, labor, and rest. It includes many details about the time monks should eat, rise, go to sleep, and how they should interact with one another. But its saintly author is adamant that “in drawing up its regulations, we hope to set down nothing harsh, nothing burdensome.” The rules are enforced with gentleness, and living life in such a structure sets one free.

This is a romantic and relaxed conservatism. My conversation with the monk was revelatory, for it showed me the lifestyle that I was seeking. Like anyone steeped in elite culture, I had been surrounded by progressives enforcing anti-traditionalist values in a stringent manner. This produced misery, for it was deeply contrary to my sensibility. For someone to show me the opposite — that I could be as deeply conservative as I wanted, while giving myself warmth and latitude — was epiphanic.

On a tour through the monastery’s library, I remember seeing titles such as “Sex in the Bible,” “The Garden of the Beloved,” and “True Sexual Morality,” and expressing my astonishment. “No topic is off-limits,” the monk said matter-of-factly. I also marveled ignorantly at the fact that I had been served a glass of Cabernet Sauvignon after lunch on Sunday. “I didn’t know you guys could drink wine,” I said. “You’ve never heard of Dom Pérignon?” the monk replied, with a wry worldliness unexpected in a monastic.

It was through these conversations that I began to understand for the first time how I could reconcile my sexuality with my Christianity, something that had always plagued me and made me feel like a fractured personality. I began to see how I could satisfy my intellectual hunger without betraying my sense of right and wrong. I discovered that I could, in fact, be integral and at peace with myself.

An article by John Pistelli in The Scroll from two summers ago noted the fracture in conservatism between traditionalists and libertines. He described the uneasy post-pandemic alliance of the religious Right and those in search of “sexual freedom or artistic license.” It’s an interesting conundrum. And one I think can be solved by recognizing one option as a set of values and the other as a mode or style through which to live those values. It is possible to be virtuous and live that virtue with a certain élan or inner release. It is perfectly possible to enjoy both “Hillbilly Elegy” and “Sons and Lovers.”

Perhaps these energies are easier to reconcile in an individual than in a political coalition. Colette, for her part, embodied a mixture. Dormann says she was “extremely well-balanced.” For all her sensuality and even laziness, she knew discipline. Her friend Germaine said “she taught me that business comes before pleasure.” (This echoes the country wisdom my grandfather, who was a mechanic, told my father, who became an artist: “Always do the hardest thing first.”) The Guardian called her “wild” and “a libertine,” yet “fitfully conservative.”

She had her first and only child, a daughter, at forty. She did not pedestalize procreation, calling it a “grande banalité.” Motherhood was part of her life, not the point of it. For Colette the primary identity was always that of artist. She described her pregnancy in animal terms, comparing herself to “a swollen she-rat.” On approaching birth: “Towards the end I looked like a rat rolling away a stolen egg.” And after the arrival of the baby: “I have a little she-rat.” She named her Colette.

Feminist attempts to craft Colette in their image have had to contend with her many inconvenient statements, including her famous proclamation that suffragettes deserved “the whip and the harem.” She was bisexual and had close female friends, but “her attitude was that of the typical male chauvinist.” Although she was not pious as an adult, her sensuality may have originated partly in her Catholicism. On a trip to Rome during Holy Week, she wrote that she was seeing “scenes of what I can only call Catholic savagery: people climbing holy staircases on their knees, people licking the shape of the cross on pavements.” Dormann says that “no note of anticlericalism ever crept into her writings … in times of difficulty she fell back on her childhood faith.” And during a dinner with Willy when she was still a young woman, she rebuked a fellow writer at the table who said that religious education had no place in schools. To Colette, this was an assault on religious freedom. “Colette shut me up,” he recounted. “She told me that I was not a true poet because poets were free, just people.” Marcel Proust was there, too, and he concurred, “arguing that he would rather see monks in the convents than ‘liquidators’ and that he did not believe in the virtues of non-denominational schools.” Proust admired the “processions on Corpus Christi day … basically, I think that is what Colette wanted to preserve too.”

In “The Cat,” a short novel about a young man who is about to be married to an impetuous young woman, Colette describes his affection for a “perfect, pure-bred Russian Blue” and his hesitancy to enter into the world of adult sexuality. The nights before the wedding are full of anxiety, and the fiancé takes comfort in his feline companion.

He flung himself on the cool expanse of the sheets, humoring the cat …

“My little bear with the big cheeks. Exquisite, exquisite, exquisite cat. My blue pigeon. Pearl-colored demon.”

As soon as he turned out the light, the cat began to trample delicately on her friend’s chest. Each time she pressed down her feet, one single claw pierced the silk of the pyjamas, catching the skin just enough for [him] to feel an uneasy pleasure.

During the day in the garden, the young man watches as the cat lusts for a bird in a nearby elm.

[She] tried hard to restrain herself; but her cheeks swelled with fury and her little nostrils moistened … He wanted to stroke the broad skull in which lodged ferocious thoughts, and the cat bit him sharply to relieve her anger. He looked at the two little beads of blood on his palm with the irascibility of a man whose woman has bitten him at the height of her pleasure.

The protagonist is not ready for the seriousness of sex, preferring to stay in the auto-erogenous zone of animal sensuality symbolized by his pet. The writer Blake Smith asserts that there is indeed an “ineradicable ambivalence at the heart of sex,” and that “the original sexual relation — prior to the one we have with any particular person — is our relation to sex itself.”

Patricia Snow, for her part, writes of “the terrifying seriousness of sex” in a January essay for First Things. Describing D.H. Lawrence as a writer whose foundational wisdom strangely aligns with that of the Catholic Church, which, almost alone in modernity, has “kept faith with nature,” she touches on “Lady Chatterley’s Lover.” The sex in the famous novel is not pornographic, as censors have insisted, “not ‘hot’ but eerily quiet, not enthusiastic” at first “but shot through with misgivings and fears. This is not casual sex. It is not entertainment or exercise, contracepted or masturbatory, looking out for its own pleasure above all.” It is instead “the kind of sex that, when certain conditions obtain, can end in new life, but even when it doesn’t, knits a man and a woman together in a relationship unlike any other.” Such sex, as Lawrence said, is part of “the solid stuff of earth.”

Life, for Lawrence, was “touch,” Snow says. And it was for Colette as well. “Connection, or real intercourse with other human beings and the created world:” everything the abomination of cyber-existence — including online shopping — would have us renounce.

In a remarkable essay called “Save Yourselves,” also exhorting us to recognize “the deep seriousness of sex” as per the editor’s subtitle, Charlie Bentley-Astor calls for a re-sanctification of adulthood. The essay may as well be called “Conserve Yourselves.” “I say and say again, save yourselves,” she chants, “for you may just save someone else in return.” It is the latest in a string of books and op-ed pieces to assert that the realm of sex must be re-enchanted, that something precious has been lost in our era of apps and casual encounters. Even prior serial monogamy, she claims, can lessen the intimacy you find with your forever person.

I concur, and can offer no protestation against the pleadings of my fellow writers for a return to the primordial sacrality of erotic exchange. I do not agree with everything they say: certain treatises are thick with denunciations of pornography, rough play, and choking. Sex needs to recover its meaning, but it must not be sanitized. Let us remember that some great works of art were first dismissed as smut. We should not surrender eros entirely. It is everywhere: in the gaze of a cat on a shop counter, in the juice of a past-ripe plum. How unsophisticated, then, to forbid the terranean pleasure of a hand placed lightly on the throat, constricting at just the right moment.