At a community meeting in 2012, when asked why she was planning to build a performance art center in rural upstate New York, Marina Abramovic replied that the architect “Rem Koolhaas has said to me ‘Real art is not happening in cities. It is happening outside cities.’” Koolhaas, for his part, mounted an exhibition at the Guggenheim in 2020 called “Countryside, The Future,” in which he explored “the 98% of the Earth’s surface not occupied by cities,” and its profound possibilities, both creative and economic.

The image of the artist is often steeped in urban aesthetics, and evokes the heroism of one who leaves the hinterlands to find the avant-garde in some great population center or other. But what if the opposite is now closer to the truth, and creative freedom is more likely to be found in the affordability and rejection of institutional strictures that rural life offers? There are many artists whose work is deeply connected to the country — Emily Brontë’s “Wuthering Heights” describes not only the fever pitch of Romantic emotionality but the rugged landscape of northern England, and Sally Mann’s controversial portraits could not have existed apart from the backdrop of her native Virginia. In recent years publications have sprung up which point to a revitalization and reenvisioning of life outside urban centers. Regain Magazine from France, a “country journal,” seeks to chronicle “the new farming generation.” “City Quitters: Creative Pioneers Pursuing Post-Urban Life” is a handsomely printed art book that describes a movement of designers, chefs, and other young entrepreneurs to the provinces.

If urban areas are now largely liberal and rural areas conservative, what does this mean for the future of creativity? Writing of “evolving positions in American society,” Ross Douthat describes present conservatism as the domain of the “increasingly disreputable, representing downscale constituencies and outsider ideas.” This would seem to be a negative, but in fact these are prime conditions for art-making. Respectability is a trap.

Martha Graham, who choreographed the ballet for “Appalachian Spring,” famously said that some of us are “doomed to be artists.” Indeed, some of us are doomed to be artists, and also to love America with all our hearts and souls.

A hundred years ago, a collection of artists known as the Stieglitz Circle — which included the photographer Alfred Stieglitz himself as well as painter Georgia O’Keeffe and composer Aaron Copland — adopted the motto “Affirm America.” Copland, a Jewish boy born in Brooklyn to Russian immigrant parents, was influenced by his mother, who had spent her childhood and adolescence among cowboys in Texas and “sang Western folk songs to her youngest child.” The spirit of Copland’s music — its reassuring optimism and evocation of vast open spaces — would come to inspire millions. “There was something about the twenties,” he said, “that tended … ‘to make us want to affirm America.’”

This Americanist art was not addressed to “the elite few,” but instead “sought to produce works that appealed to mass audiences, works that spoke to a wide variety of individuals during difficult economic times.” Perhaps it is time for a new group of artists to adopt an attitude of America-affirming care. Before I left New York, a gallery had opened on the ground floor of my building that featured photographs of burning cop cars and other motifs characteristic of the anti-patriotic posture that is now a prerequisite of the creative class. That shit is tired and we all know it. It is time for our own twenties, and for something new.

Aesthetic Notes

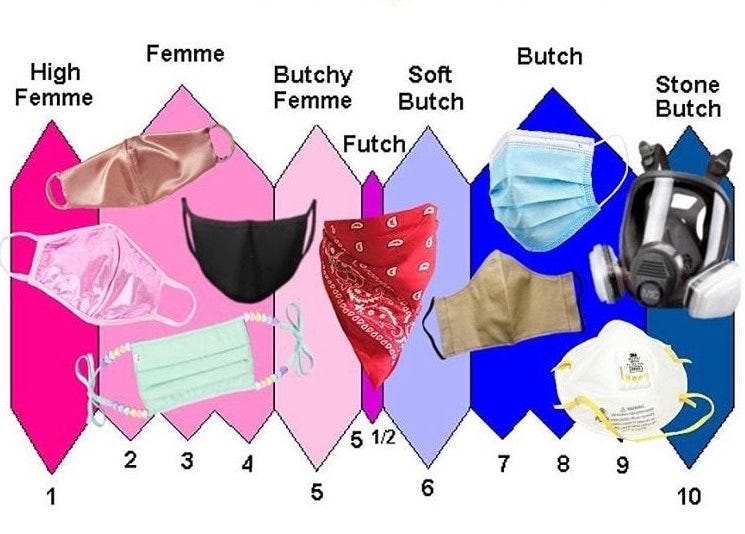

Several years ago, I came across a chart explaining various categories of femininity and how they correspond to assorted phone chargers. If you are the type of person who immediately recoils at any discussion of “gender identity,” you may want to stop reading now. In any case, this meme came in a variety of flavors, with degrees of girldom finding expression in everything from masks to manicures.

It occurred to me that the “futch scale,” as it is known, could apply to the variegations of rural feminine identity, each of which I have inhabited at various points in my existence. Aesthetic examples are to be found in contemporary culture. Corsetry and cottagecore are pastoral high femme:

A song like “Redneck Woman” by Gretchen Wilson (lyrics include Victoria's Secret, their stuff's real nice / But I can buy the same damn thing on a Walmart shelf half price) is a futch country artifact:

And Sarah Palin, God love her, is butch country at its finest. Femme country is for sniffing flowers, futch is for drinking beer on your porch, and butch country is for shoveling shit in your Carhartts.

Something else I’ve noticed recently is how much food photography and cuisine presentation have changed. A few days ago, while rummaging through one of the Little Free Libraries in my neighborhood, I found a copy of “The White House Family Cookbook” next to a novel by Stacey Abrams (who, much like Beta Male O’Rourke, will hopefully join the pantheon of politicians we now have respite from).

Everything about this table — from its profusion of flowers to its meat topped with distasteful goo — its assortment of cutlery, and the complicated crystal glasses — is the screaming opposite of how modern food is photographed. Nowadays, kitchen interiors and recipes are shot like this:

Honestly, why is that? Who wants to sit in a darkened room eating artisanal squash? With a fork that looks like it could give you tetanus if you put it in the wrong orifice? The “Family Cookbook” presentation, assembled and published in 1987, at least looks convivial. It seems like the kind of table you could have an uproarious conversation over, maybe get your shirtsleeve stained with something savory. By contrast, the faux-minimalist, beige-infused tableaux of today’s culinary life are seriously wanting.

Happy Thanksgiving, friends, and God Bless America.