America's Beating Heart

At this point in my life I have perfected the Church Walkout. It’s a bit like the Irish Goodbye, except it doesn’t take place in a bar and it’s far from inconspicuous. Still, I try not to make a display of myself. I usually sit in the back, hoping that this time, this church, will be The One, and when it isn’t, I’m out of there like Julia Roberts in Runaway Bride.

The last time it happened was at a Baptist church, two days after the Dobbs decision. I arrived early and sat in the third or fourth row this time, thinking I would be safe. Surely, in a Baptist church, I thought. But no. A staff member stood up and explained that the pastor was absent that day, and that various other people would be leading the service. Not two sentences later, he lamented the loss of a constitutional right to abortion in front of the entire congregation, shrugging his shoulders in an act of helpless despair. Here we go, I thought. I considered how tightly my shoes were tied and plotted my imminent escape. But, but! He pled. “We encourage you to stay, even if you might hear some things you disagree with,” and offered assorted platitudes about “these trying, tense times.” Begrudgingly I sat still, the bile rising in my throat, until a guest giving the sermon raised a surgical mask high above the pulpit, preaching about its virtues as though it were a holy relic. That was my cue to leave. As soon as he uttered his last admonishment, I fled the sanctuary, crossing my name off the contact tracing list I was constrained to sign upon entering. I should have known this would be one of those churches, I said to myself. The pastor had “she/her” listed after her name.

I’ve encountered many such churches in the past few years. I’ve been trying to find a place I can worship. And being Protestant, and an Evangelical at heart, I have sought solace in a multitude of congregations, each one more bewildering than the last. There was the Methodist church that had a huge banner of a Buddha-like figure meditating to the left of the altar (weird flex, but go off, I guess). There was the Episcopal church that devoted itself to the poison that progressives call “anti-racism.” There was even a Catholic church where the homily veered into a postmodern acknowledgment of “many truths,” ignoring Christ’s claim to be the truth (John 14:6).

All of this is perhaps part of why I found myself, last fall around this time, driving deep into the heart of New York State, to find the land my family is from. I needed to see where my grandparents were buried. I needed to understand why I had come to feel so out of place in the city I’d lived in for years, why everything seemed to be coming apart at the seams. I remember driving through Albany and the strip malls at its periphery, stopping at a red light every sixty seconds, desperate to get beyond the traffic into some kind of country I recognized. And then it happened. The spaces became more open and bales of hay were visible in far-off fields. Cars were fewer and those who passed me drove lifted pickup trucks. Church steeples poked out from towns in the distance. And finally, when I did stop at the intersection of two county routes across from a convenience store, I found my salvation: a single sign on pastel paper stapled to a utility pole that said ABORTION IS MURDER.

It was like the scales fell from my eyes, and thirty years of weight fell from my shoulders. Here, I can be myself. Here, I do not have to pretend. I do not have to live a double life, constantly assenting to things I know to be false. I have reached the other side of the looking glass. I am at home and I am free. The relief is instant. I drive by a letterboard that says PRAY FOR AMERICA, and when I find my family, a niece of my grandfather’s that I haven’t seen since the funeral, I hear myself code-switching to Jesus-speak.

“That was the Spirit that told you to write that,” she said to me once after I fretted about a text message. “God is in control,” she’d sigh after talking about a frightening situation. The ability to say “that was God” after a blessing or “if it’s God’s will” when talking about a desired outcome and know that no one would look at me cockeyed was a revelation. The effects were physical, like years of armor being taken off the body, like everything clicking into place.

I am starting to understand why I have felt so lost for so long: because a world in which the heartbeat of an unborn child is referred to as nothing more than “a primitive tube of cardiac cells that emit electric pulses and pump blood” (as per The New York Times) is not a world I want to live in. The incomprehensible evil of a politician who claims that evidence of the beginning of life is nothing more than a “manufactured sound” is not something I can stomach. Is the passing of a soul no more than declining respiration and the shutdown of vital organs? Are two teenagers in love for the first time merely reacting to a flow of norepinephrine and vasopressin?

It seems to me that the essential question is not one of forcing people to comply with laws or whether to amend the constitution but how we as a people have arrived at a place where the conception of a child is seen as having no deeper meaning. How have we arrived at such a state of spiritual emptiness that life is seen as something simply mechanistic?

Even Christopher Hitchens, a fire-breathing atheist, spoke favorably of the “essential dignity of the right-to-life position.” His misgivings about abortion were deeply instinctual: “I had a queasy feeling about the disposability of the fetus. This queasy feeling has not gone away.” He argued that we inevitably have a “basic reverence for life” and added, interestingly, that “nobody on the left can avoid noticing that the so-called ‘prolife’ forces are overwhelmingly female and from income groups that traditionally voted Democratic.” He calls this a “simple rebellion by what one might dare to term humble people.”

Hitchens was not the only person with leftist origins to critique abortionists. Several months ago, I ordered a “Roe Gravestone” pin from Progressive Anti-Abortion Uprising, a young feminist group in favor of “increasing social support for women and for parents.” PAAU’s leaders look like the young activists you might see at any march or protest, and list other commitments in their bios: veganism, prison abolition, climate justice, and a consistent life ethic. In September, The New York Times ran a headline saying that “Russian Trolls Helped Fracture the Women’s March.” But the Women’s March fractured itself — on January 16th, 2017, it removed the pro-life group New Wave Feminists as a listed partner, and made perfectly clear that pro-life women were not welcome. It’s difficult to describe the way my blood feels full of venom when I hear again and again that “we as women must stand up for reproductive rights!” or “we as women must fight back!” on call-in shows, or the rage that courses through me when people like Madeleine Albright say things like “you have to help. Hillary Clinton will always be there for you … and just remember, there’s a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other.” It is difficult in the face of such authoritarianism to think anything other than, with my last breath I will defy you.

In the days after Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election, I remember a rapid change happening in my industry. I had been working in retail for several years. Fashion was my natural home and a community I wanted to be part of forever. I liked selling and I was good at it. I could have sold a used handkerchief if I wanted to. I loved receiving clients, talking to them about style and their lives, and thought about going more deeply into fashion business or becoming a fashion journalist. But there was something in my soul that could not abide each time an employer put a Planned Parenthood sign in the window — like a record scratching, it reminded me constantly of an atrocity I am expected to consider normal, an alert that if these people really knew who I was, I would not be welcome. I’m not here to assent to the killing of children, I’d think. I’m just here to sell clothes.

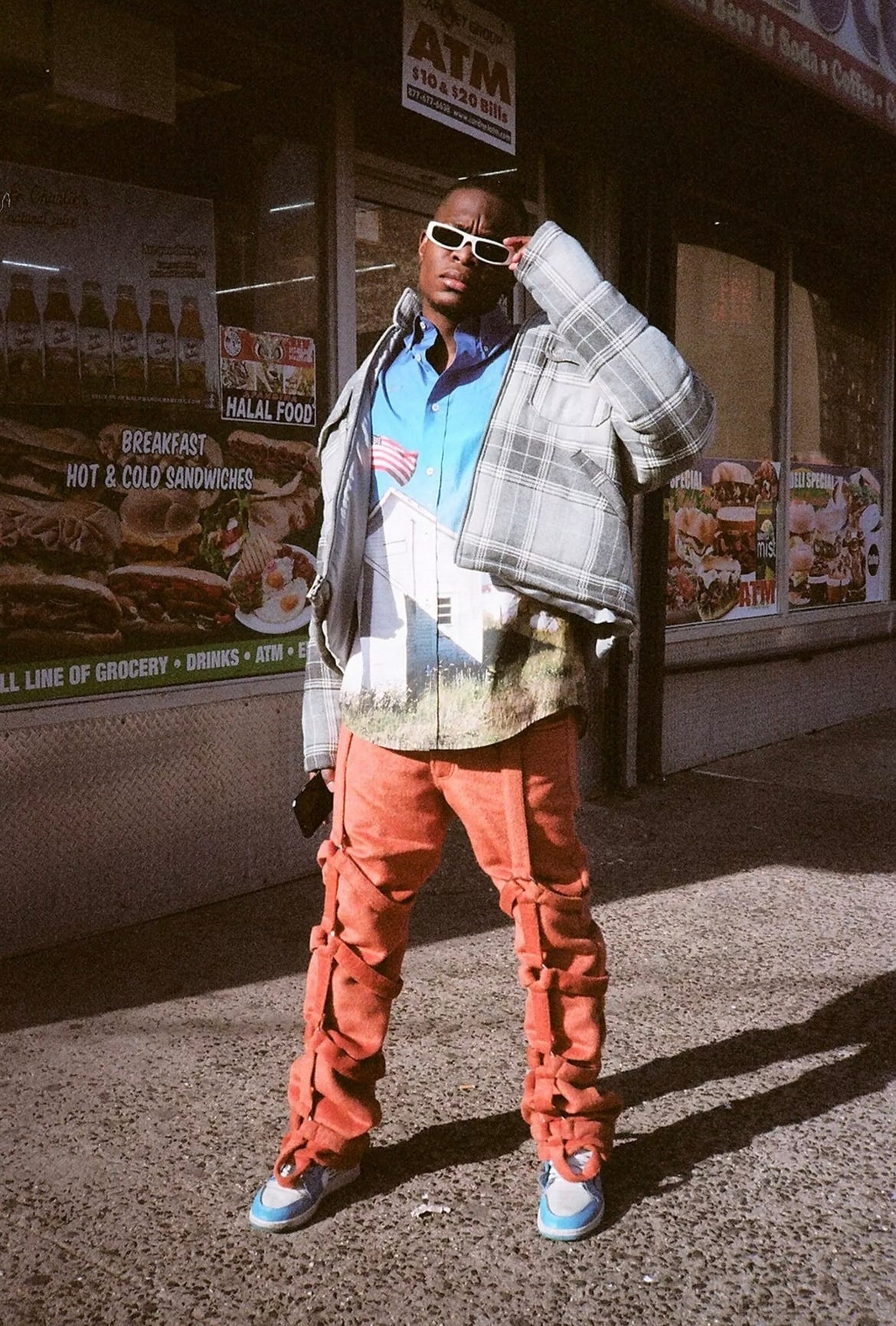

In 2019 the streetwear website High Snobiety profiled young fashion designer Everard Best, a protégé of Virgil Abloh and Heron Preston. At first describing graphic tees and hoodies, the piece takes an unexpected turn when Best begins to talk about God. Relating a difficult past, he takes seriously the directive Christ gives in Mark 5:19 when he tells a healed person to “go home to your friends, and tell them all the great things the Lord has done for you.” The interviewer acknowledges that “speaking publicly about faith isn’t exactly the norm for designers,” and that the artist’s candor might “lose him some fans.” It might result in a loss of business, a change in direction, or his designs not being stocked in prominent department stores. But Best is adamant. “Because I’ve been in deep, dark places and the only thing that saved me was my firm foundation in God,” he says. “If I could go through that, then why would I be selfish with that information when I could help the next person who’s been going through deeper, darker places than I have? If I could help them, then that’s worth way more than being in Barneys.” Amen.