In 2014, an young artist named Nayvadius DeMun Wilburn released an album called “Honest.” It was in many ways his first introduction to a wider public, after an Atlanta adolescence spent making mixtapes as part of the Dungeon Family collective. A commercial release, “Honest” was full of pop star collaborations, and came at a time in the artist’s life when all things were looking up: he was also recently engaged to fellow celebrity Ciara, with a baby on the way.

Sometime in the summer of that year, things went south. There were accusations of cheating, and the engagement was called off. By the next year, Ciara and her ex had gone in drastically different directions. She started dating Christian athlete Russell Wilson, speaking publicly about the couple’s abstinence until marriage. And Nayvadius, now the creative force known as Future and one of the most prolific musicians of his generation, had penned the infamous lines:

I just fucked your bitch in some Gucci flip flops

I just had two bitches and I made them lip lock

I just took a piss and I seen codeine coming out

He continued, presumably alluding to Ciara:

Bitch, I’ma choose dirty over you

You know I ain’t scared to lose you

They don’t like it when you’re telling the truth

I’d rather be realer than you

After the harmless “Honest,” Future had returned to his roots as a documentarian of the darker elements of human nature. Naming his new album “DS2,” a reference to an earlier mixtape named “Dirty Sprite,” he explained breaking away from an atmosphere in which he felt stifled: “I’m not comfortable about where I’m at in my career. I’m not comfortable about compromising and about being the person that I am and being the man that I am. I feel like my better judgment is to go back to record and make music. Make the music I know the people want. I know they want that ratchet shit from me, I know they want me to say the most disrespectful shit. I came in like that.”

“DS2’s” opening instrumental passage sounds like the long descent into a crypt, in which one passes by cobwebs on the way to an inner chamber where there is ever less light, and finds the artist ensconced in a swivel chair— Dr. Evil style— as he turns around and tells you who he really is, now that respectability no longer burdens him.

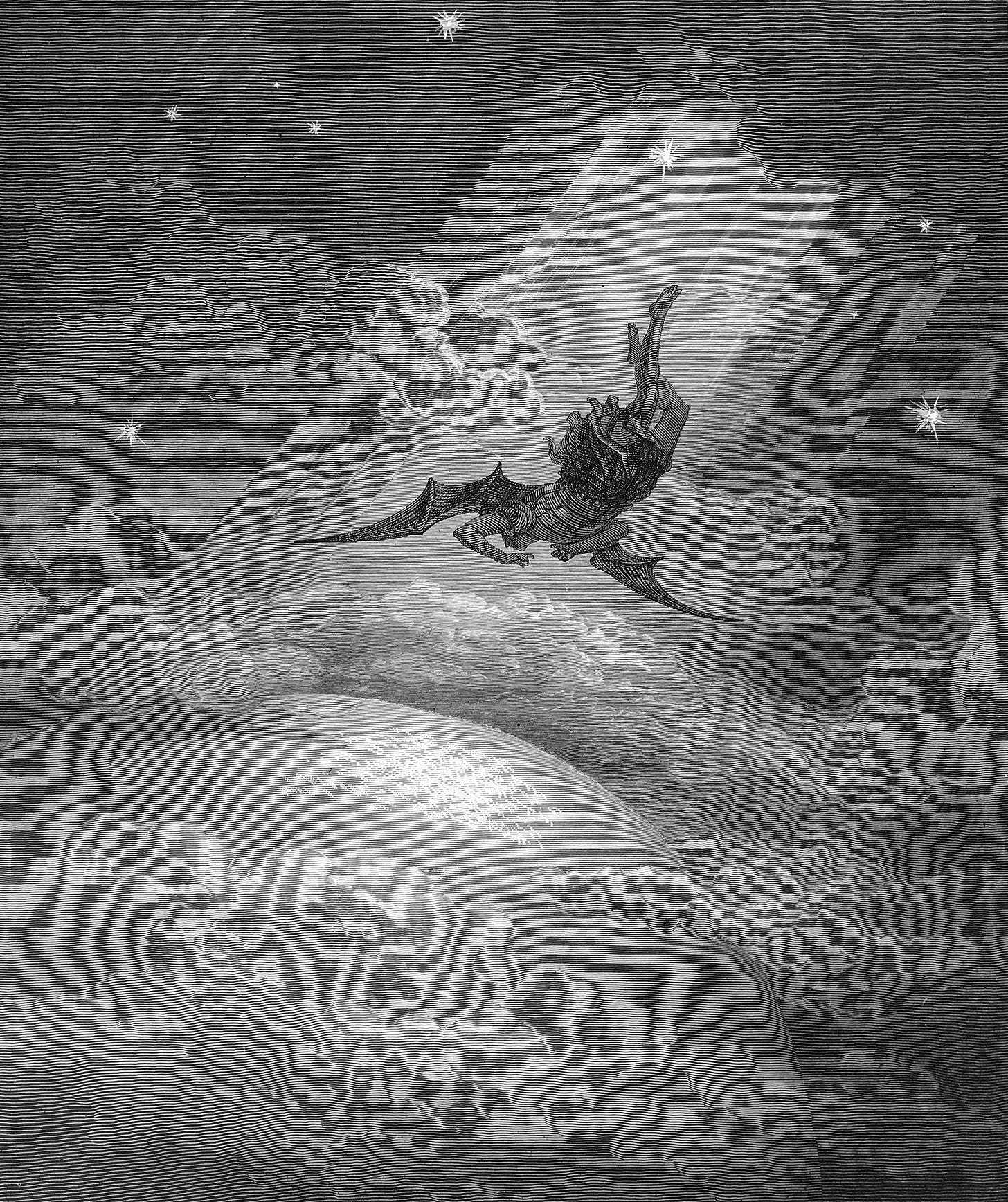

It was this moment that marked Future’s liberation, and set into motion the epoch-defining works of the years that followed. He had perhaps discovered one of the eternal truths about creativity that Romantic printmaker William Blake talked about in his 1790 publication “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.” In writing about metaphysical poet John Milton, the author of “Paradise Lost,” Blake claimed that “the reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when he wrote of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it.” Milton’s depiction of Satan is charismatic and compelling, the way Future’s “DS2” is in comparison to the people-pleasing flavorlessness of “Honest.”

There is something Satanic about being an artist. The aesthetic impulse is inherently perverse. And creative people, in order to be free, cannot worry about being on the side of the angels. The proliferation of socially approved art that characterizes our era, as emerging writer Alice Gribbin describes so precisely in her essay “The Empathy Racket,” seems to be reaching its nauseating peak. Contending that “the imagination cannot be restricted without consequence,” Gribbin rails against all that “domesticates, sanitizes,” all that is “spirit-smothering” and “tyrannous.” A writer cannot dare to speak the truth if she is simultaneously paranoid about producing something that adheres to the authoritarian dictates of the social justice regime. The Marquis de Sade, a libertine of the eighteenth century who endured long prison sentences as a consequence of his merciless erotica, once said that “Sex without pain is like food without taste.” I would add to his statement: art that dares not offend is not art at all.

In her excellent book “The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning,” critic Maggie Nelson explores the transgressive art that characterized the twentieth century, and wonders aloud if it can ever be reconciled with the wish to achieve a more peaceful social order. Her conclusions are complex. She acknowledges that “work that has no designs on eliciting compassion or bringing about emancipation can be the most salutary, the most liberating.”

I predict that in coming years increasing numbers of eccentrics whose imaginations cannot be restrained will abandon the empty tower of socially responsible art. Scorn and shock will accompany their expulsion, but the descent, like Lucifer’s, will be strangely thrilling.

If the creative impulse is inherently Satanic, does this mean that Christians or other people of faith can’t be artists? Of course not. Much of the great art that has existed across centuries is religious in nature.

God creates artists. He knows that on some level we will be rebellious, dissident.

And He forgives us.