In 2023, the most listened-to items in my Music app were “Meditabor in Mandatis Tuis” (“I Will Meditate on Your Commandments”), a choral piece by the Counter-Reformation era Italian composer Palestrina, and a 1986 EP by the Cocteau Twins called Love’s Easy Tears.

Meditabor in mandatis tuis, quae dilexi valde:

et levabo manus meas ad mandata tua, quae dilexi.

I will meditate on your commandments, which I have loved exceedingly:

and I will lift up my hands to your commandments, which I have loved.

First published in 1593, this short composition for five voices (typically sung on the second Sunday of Lent) arrived late in the life of a composer who had experienced great acclaim as well as personal tragedy. Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina lost a brother, two sons and his wife during European plague outbreaks in the 1570s. In despair, he entered more fully into his faith and considered becoming a priest. Eventually, however, he remarried, and the wealth of his new spouse allowed him to compose with ever-deeper dedication. Officially employed by the Catholic Church in his day and in musical service at the Vatican, he is acknowledged as the institution’s greatest-ever composer.

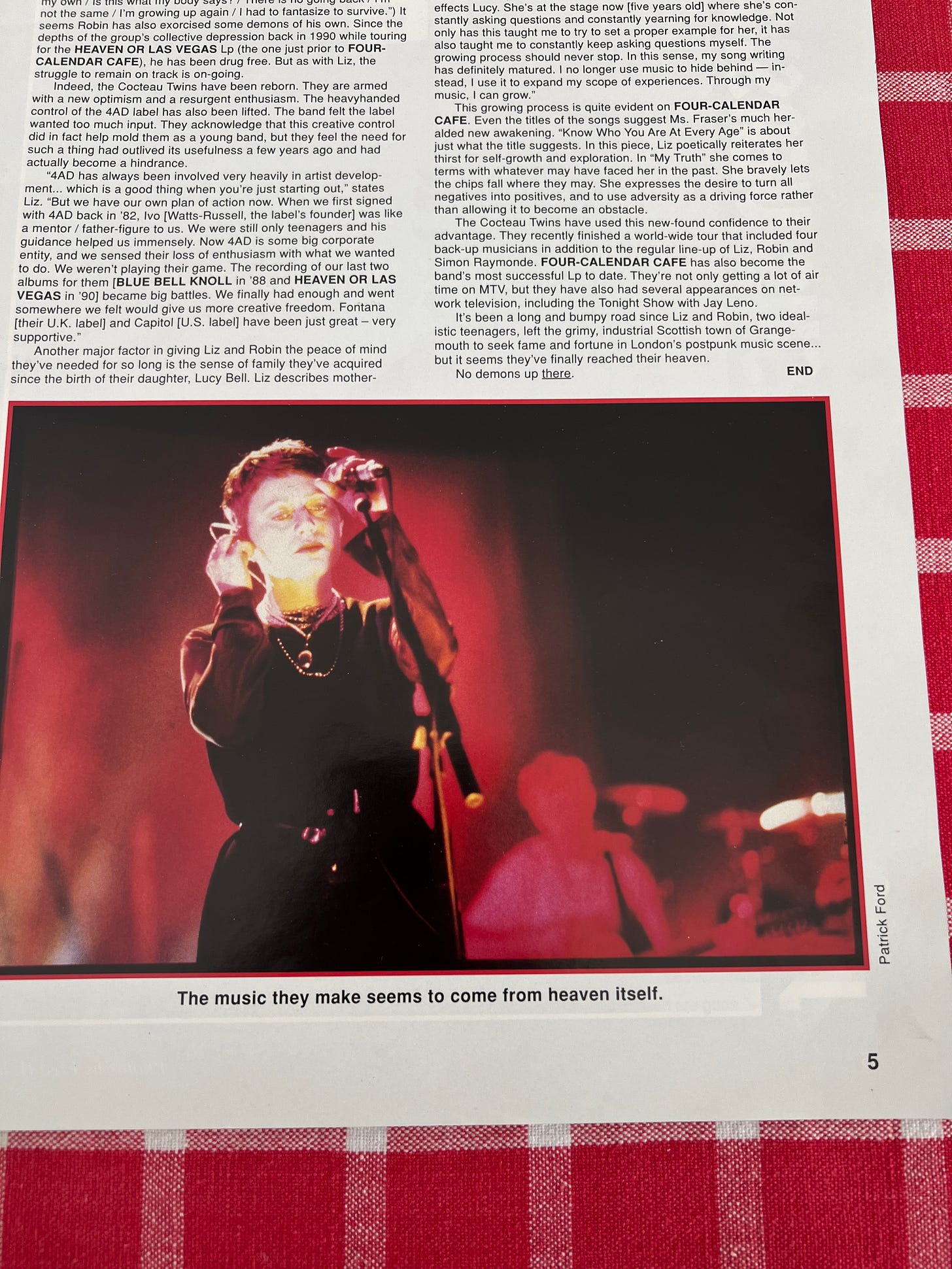

Love’s Easy Tears, an exultant four-song collection by a band that emerged from the shadows of gothic postpunk, showcased a Cocteau Twins somewhere between the pagan gloom of Garlands (1982) and the celestial happiness of Heaven or Las Vegas (1990). The EP is perhaps a conversion point in a trajectory that saw the trio, fronted by singer Elizabeth Fraser, evolve from the witchy sludge of their first outpourings to the ecstatic, almost ecclesial sound of their later albums. Propaganda, a long-defunct goth subculture mag, described them in a 1995 profile as “the defining statement on what is ethereal and eternal in pop culture” — “from no quarter of the cosmos echoes a more angelic sound.” Fraser experienced it differently from her audience, however: there is “a lot of anguish and aggression” that went into the music, she said. What for some on the outside sounded like serenity, “for its creators” was “a by-product of self-torment and self-doubt” (this echoes author Steven Pressfield’s statement in The War of Art that “the artist committing himself to his calling has volunteered for hell, whether he knows it or not. He will be dining for the duration on a diet of isolation, rejection, self-doubt, despair, ridicule, contempt, and humiliation”). Still, the profile ends with an acknowledgment that the Cocteaus seemed to have “finally reached their heaven. No demons up there.”

What is interesting is that both of these sources of music, which couldn’t have come from more different places (one a papally-employed Renaissance polyphonist, the other a punk band from post-industrial Scotland) express the miracle of divine presence and a profound sense of spiritual release. I have always thought of Elizabeth Fraser’s voice as the inner expression of Mary, the mother of Jesus as she exclaims the Magnificat: My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God, my savior (Luke: 1:46-7).

Why would God call such different voices to express His reality? Why does He call some to official service of the Church and others to labor in secular fields, bringing a sense of the celestial to those who would otherwise never hear it?

In 1952, an obscure French scholar named A.M. Goichon published a book called Contemplative Life in the World. The translator’s preface to the 1959 English edition carries the message to readers that “in this age and time God seems to be calling more and more men and women to contemplation outside the ordinary religious framework.” Contemplation, a deep union with God through prayer which was previously thought to be the aim of only those in the cloisters, appeared to be progressively “find[ing] a home amid the natural social groupings of industrial workers, rural folk, clerical workers, officials, professors, students, intellectuals, and artists.” Why would people in such unexpected places be drawn into a mystical “supra-temporal conversation” with God (a conversation outside of space and time)?

Mlle. Goichon says that the reason God leaves contemplatives in the world is so that they may bear witness to the Unseen God and to the possibility of a personal friendship with Him, thereby drawing many others to a more intense spiritual life.

Contemplative Life in the World is an enormously useful guide for anyone who feels drawn to deep levels of meditation, time spent alone with the Divine, and desires to bring back the messages he hears to those around him. There are people, misunderstood by society, who long for peace and quietude — who may be perfectly content to be solitary — and who should not seek to change themselves to match the loud, garish ideal of our day. Such people are contemplatives. Contemplation is a gift.

The monastic life was founded with the ideal of leaving “one free to pray and work in silence most of the time.” But Goichon’s book illustrates how many people, despite their state in life, might try to dedicate some time to this pursuit. There is “reason to hope that the contemplative life in the midst of the world is not an illusion or a pulling in opposite directions,” she says. The most important thing is to recognize that “the turning of the mind and heart toward God naturally induces us to avoid whatever distracts our attention from Him.”

I do not know all that being a contemporary contemplative in the world entails, and certainly I fall short of it myself, but I do know one thing it requires: freedom from the internet.

I should say, with more exactitude: freedom from excessive use of the internet. No one can avoid online activity in our era, unless she lives in a cave or under a rock. And since we are not salamanders, but human beings, we must allow ourselves a certain latitude to pay bills, complete our work, and communicate as needed. But anything past this can be discarded with more ease than most people suspect.

In my last essay, I wrote about the concept of digital chastity. It’s not in reference to erotic content, per se, but represents a right-ordering of one’s internet use. It’s not the same as digital celibacy, which would imply no internet use at all. In digital chastity, one only uses the internet for things one is firmly committed to (like working or writing, for example, or scheduling doctor’s appointments for a loved one), forsaking all the rest. Such structures, like monasteries as Goichon describes them, “are not prisons, but fortresses of liberty.”

Such an inner cloister is a “framework where a liberating void replaces the cloud of useless thoughts that buzz like flies and stick to our slightest activities.” Is there any better description than all of X and frankly half of Substack Notes? Even if I only spend 45 minutes a day on X and Notes combined, that’s 45 minutes I could have spent reading In Search of Lost Time, or taking care of an animal, or walking in the woods.

Why are writers expected to be Extremely Online? What would the voice of an Offline writer sound like? Wouldn’t it have a greater chance of attaining to posterity, a greater chance at longevity than writing whose commentary is sprinkled with Twitter lingo no one in 200 years will understand? Shouldn’t more writing, like prayer, be supra-temporal instead of hyper-temporal?

I find myself enraged at suggestions that I must simply submit to technological progress as though I had no free will, no dignity. I rebuke them with all of my life force. “Submit.” Why must I? Is there a law that says I must? Is this truly a prerequisite for the vocation of writer? Like Walt Whitman, I “dismiss whatever insults [my] own soul” and I “hate tyrants.” Technology is a tyrant. I simmer with resentment at the Notes-ification of Substack, my beloved canvas. I want nothing to do with it. “Yes, but you promote your writing there,” a detractor will quip, ending his provocation with a Beavis and Butthead-esque chortle. “It’s important to find balance,” a wellness-minded person might caution. “Yes, but in order to find balance you have to experiment with extremity,” I answer (my father, a William Blake fanatic, taught me well: the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom).

Writing is not, and should never become, social media.

I reject the proliferation of robots at the store. I refuse to tally my items in the glare of their blinking scales and scanners. At every opportunity, I choose to engage with a human worker instead. “Have a nice evening, dear,” the woman at the register said to me a week ago, placing my mandarins and honey in a brown paper bag. Even if a robot could call me “dear,” would it feel the same?

Since I have started detaching from the internet, my dream life has grown wilder. It is more easily remembered. Two weeks ago I woke in the night and wrote this down: I dream that the small constellation of people I know in DC is known not as the Deep State, but the Deep Church.

Perhaps the role of a religious artist, or of anyone who witnesses to God while living in the world, is not to choose between Heaven or Las Vegas but to simply dwell in, and remain connected to, both of them. This would certainly be an illustration of the Catholic (and overall Christian) principle of “both/and.” One can see this sentiment in the video for U2’s “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” filmed in Sin City in April 1987. “I believe in the Kingdom come … You loosed the chains / Carried the cross / Of my shame / You know I believe it,” Bono sings, in front of a sign that says “Today! FREE LIQUOR WITH JACKPOT.”

The contemplative life in the world implies the meeting of two universes. It is not closed to the world, but remains immersed in it, taking on the traits of its own time, sharing its difficulties, its cares, and its sufferings. However, it simultaneously abides in the peace … of a love that has already [reached into] eternity … the realms of earth and heaven are in no sense separated in such a life.

Perhaps the most radical thing one can do is speak the name of God in a place where God doesn’t belong.