On March 19th, 2024, beloved Belgian fashion designer Dries Van Noten announced that he was stepping down from his eponymous brand. After an almost 40-year career, his last show happened in Paris three weeks ago, and many reported that the room was full of emotion. Dries’ designs meant something to people and became part of their intimate lives: he is famed for his clashing prints, inventive fabrics, and craftsmanship, as well as his eminent wearability. Owning a Dries piece signals good taste and subtlety. “I tried to make things people would cherish,” he shared at the pre-show party.

In the age of an ever-accelerating fashion cycle, in which the idea of “product” reigned, Dries’ creations represented the artisanal. In the slate-grey heroin-chic 1990s, his clothing blossomed in color and his models smiled on the runways. He employs a team of specialists so his embroidery can remain handmade. He deplores the term “fashion,” which implies an item that can be thrown away after six months, preferring to make clothing which is “growing with you — as a person, as a character … which can become part of your personality.”

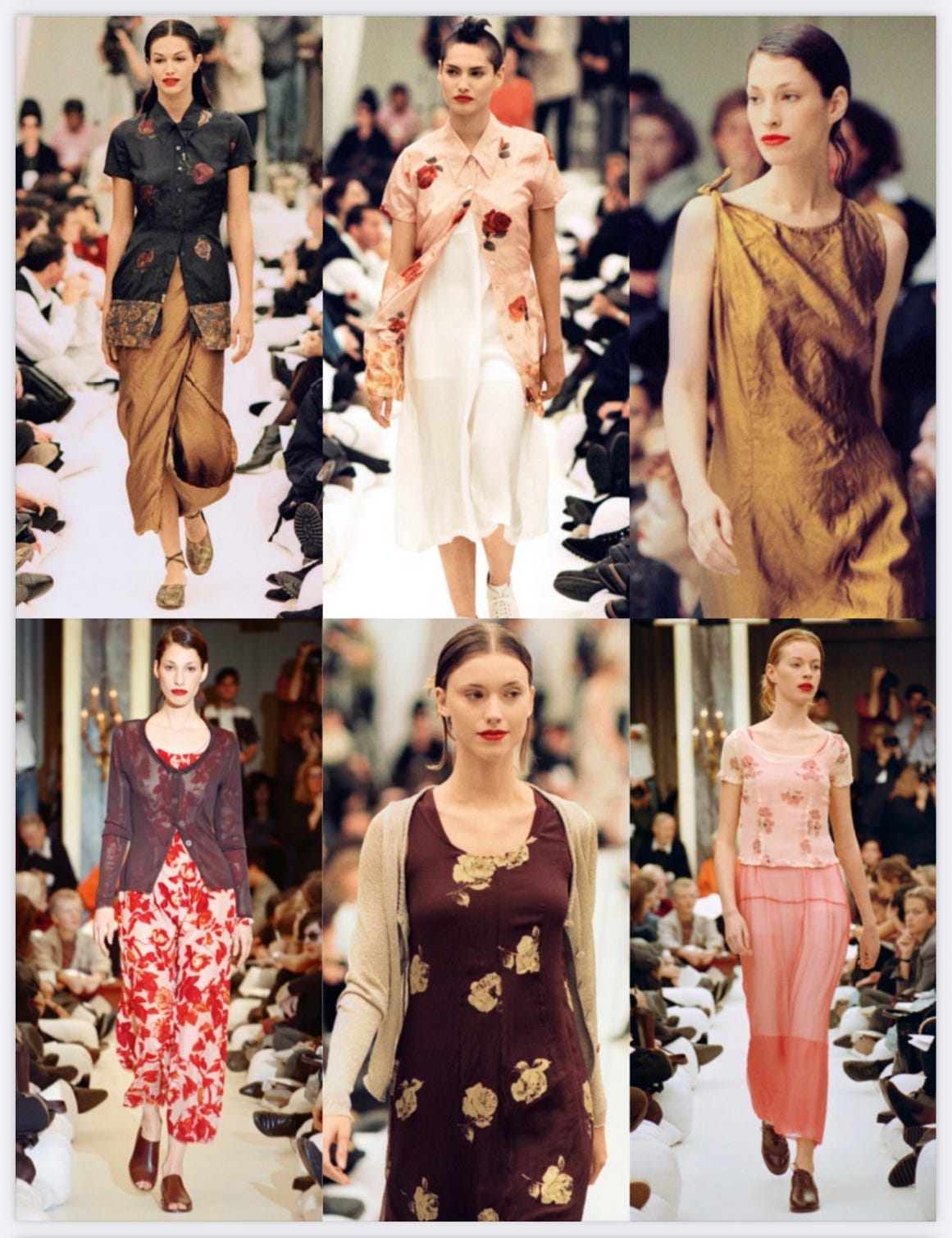

His collection called “Flowers,” for the 1994 Spring/Summer season, created a reaction that made the young Van Noten a critical and commercial success. Describing the post-show craze in the 2017 documentary “Dries,” he talked about his reconception of materials. “It was the first season I started to work also with prints,” he explained, which “were all on silk and georgette” and other delicate fabrics. “Silk was always considered as a material to be worn on special occasions, but not just as easy daywear. So what I decided, in fact, was to throw the whole collection in a washing machine.” This gave the garments a “wrinkled, shrunken, casual” feel that made them appropriate for female clients to wear in daylight hours. It was a punk move, especially for someone of Dries’ classical education and natural restraint.

Watching the runway presentation now in all its hypnotic movement, every piece still feels modern and covetable. I am struck by the warmth in the show — the laughter of the young models, their unhurried gaits, the haphazard way the press is sitting on the floor, and the genius touch of having male-female couples present dual looks at the finale. This is a relic from a time when the fashion industry had not yet adopted that air of hyper-exclusivity which entrances some and repels others.

Forced to garden as a child, which he says he “hated,” Van Noten developed a familiarity with various plants and their growing cycles. It was as if, with his explosive 1994 collection, he had finally figured out how to transform flowers into people. There’s a poignancy to Dries’ designs — their beauty is exquisite, but one is reminded that a person’s flowering is ephemeral, too. A garment associated with a romantic moment or sweet memory is special because the moment has passed.

The combination of grace and experimentation that exists in Van Noten’s work is perhaps the result of his austere Jesuit schooling and his participation in the avant-garde 1980s Belgian fashion scene. At design school he met other young talents like Ann Demeulemeester and Walter Van Beirendonck, with whom (among others) he formed the Antwerp Six: a group of influential minds who put their unlikely dwelling on the fashion map. At that time, “Belgium was, I think, the most unfashionable country in the world,” Dries said. But if you’ve ever questioned whether a small group of people can ignite a cultural fire in an unsexy outpost, this cohort is proof.

Van Noten’s way of working — the kindness with which he treats collaborators, the calmness of his demeanor, his placid walk among fabrics spread across his studio — is evident in the documentary. But the way he describes his own mind is quite the opposite. “People always ask me, like after all those shows, is it not getting more easy? No. Forget it. It’s not getting more easy … you always have to go through a battle to obtain certain things.” He talks about his ranging eye: “I look the whole time. In that way I think I’m not always the most easy person to live with, because I — the whole time, I’m looking, I’m thinking, it’s a machine which doesn’t stop.” He lives in a Neoclassical house outside Antwerp with his longterm partner Patrick, and the interiors, gardens, and grounds of the property are an aesthetic project of their own. “Everything [we] are doing in life is done with a lot of passion … the way we live, it’s very intense … Sometimes we suffer also from it, that we are maniacs in details.” He is unable to look at photographs of a show upon its completion. “For me it’s always very difficult to be confronted when the fashion show is over with the images of the fashion show … I don’t want to see the video straight after the show, I can’t. I can’t confront it. I think I’m too perfectionist to live with that. I see a lot of mistakes, always … that [makes] me maybe not always the most happy person, but it makes me the person I am.”

He is realistic about the demands of being a working artist. “Success creates more pressure, because of course, people expect also always more and more and more. It’s not always getting more easy when you’re getting better known … No. The pressure is getting sometimes also more important.” Is it exhausting? “Yes. Of course, I think it’s — when you do something passionately, you go really until the limit. And sometimes I think you cross also the limits. And that’s not — it’s not always easy.” “What do you do against it?” The interviewer asks. Dries’ answer is simple: “Suffer.”

This, to me, seems like a beautiful acceptance of the Cross of being an artist. The way the world catechizes us — “don’t be so hard on yourself!” — is often the opposite of what an artist needs to hear. In his book “The War of Art,” Steven Pressfield says as much in a section called “How to Be Miserable.” Like Van Noten, who was schooled by Jesuits, Pressfield experienced severity and discipline in his youth: he was in the military. Such a background, he says, “teaches you how to be miserable. This is invaluable for an artist … The artist committing himself to his calling has volunteered for hell, whether he knows it or not. He will be dining for the duration on a diet of isolation, rejection, self-doubt, despair, ridicule, contempt, and humiliation … He has to know how to be miserable. He has to love being miserable … Because this is war, baby.”

Dries speaks of the moment when a look comes together. “We always call it ‘addiction’ and I think it’s an addiction — just that you know that you can create a moment of beauty and that you can create an emotional moment … when you do a fitting and you say” — he makes a clicking sound, and a hand movement that implies he has grasped something — “I have it.” This is the way I have heard addicts describe the moment when a drink overcomes your thoughts and dissolves them into oblivion. It is also what happens in meditation when, after a few minutes of stillness, you become subtly aware of God’s presence. Your soul drops down another level, and you’re in the deep. It is the moment when a kiss begins to alter your brain chemistry. Or when a writer stops “thinking” and the words write themselves.

It’s worth it.