My Time With the Satanists

On unlikely friendships and bad influences

I remember the first time I went to a goth club. I was 26 years old, and I had spent the evening devising the perfect outfit. The aesthetic preparation took about two hours: first I bathed. Then, I put on the clothing I had laid carefully on the bed, starting with black undergarments. I had chosen a long black skirt with a tulle overlay, accompanied by a black corset over a gauzy grey camisole. I wore hair extensions to make my already long hair reach below my hips and spent twenty minutes lining my eyes with black, over and over again. When that was done I lay down, breathed deeply, and squirted myself three times with perfume — Tom Ford’s Black Orchid.

My arrival at the goth club was somewhat less successful than the preparation. Once outside, I could not bring myself to go in. I did not know any other goths, and I had found the listing for this club online — not by word of mouth. I did not know what to expect. I stood there, on the sidewalk covered in discarded gum, all geared up (so to speak) and looked into the doorway. I could see other shadowy figures mingling inside. Were these people like me? Did they share my longings, my dissatisfaction with society? Would they accept me?

I never entered the club that night, but I would return. Eventually I became a part of that community — the small collection of ne’er-do-wells and outlaws that frequented weekly Wednesday night gatherings. Since most goths did not have regular 9-5 jobs, they could permit themselves to party on a weeknight and only be getting started by about 11 P.M.

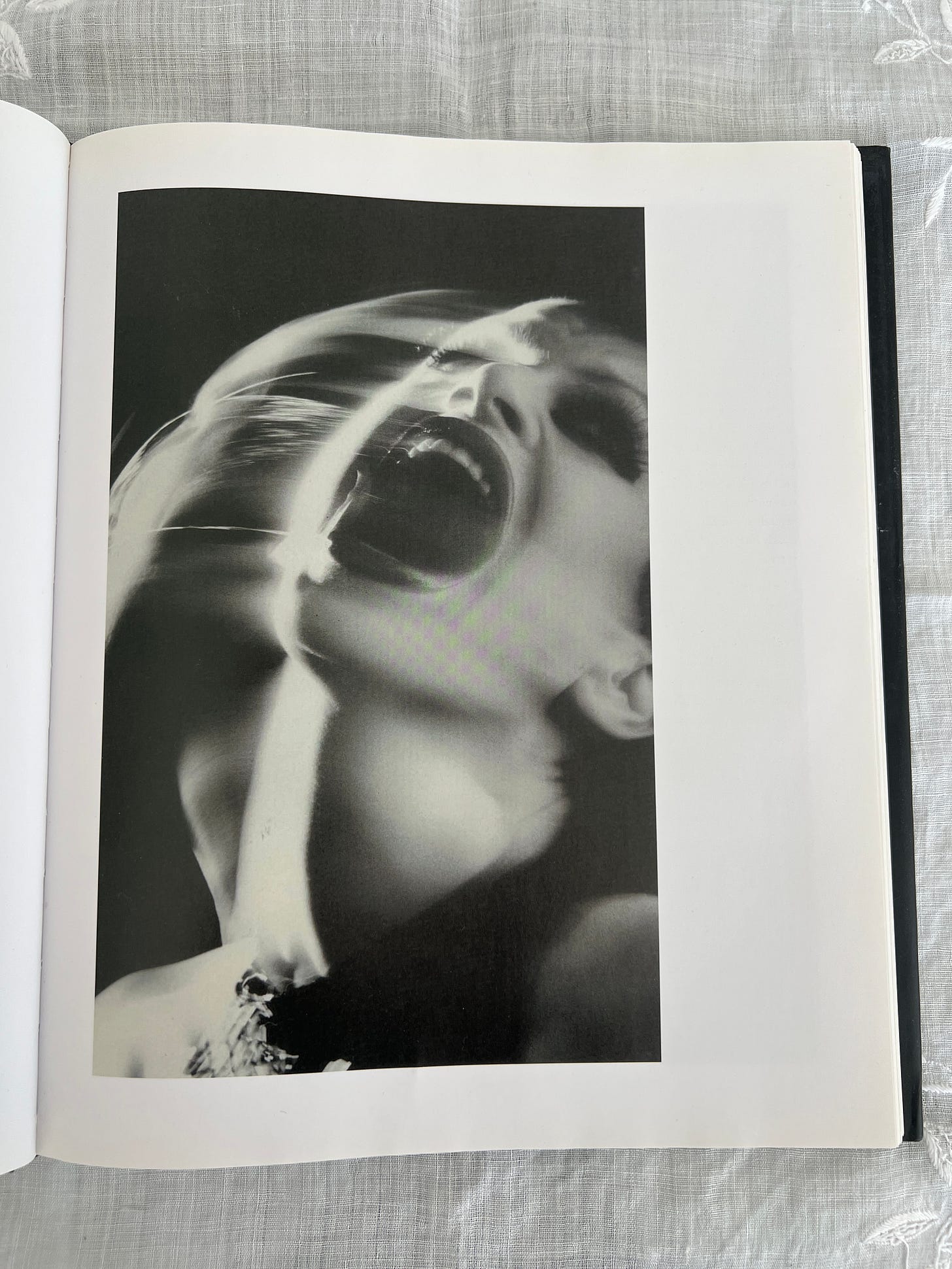

Most of the goths I met were exceptionally kind people, if a little rough around the edges. And without employing a much overused word that starts in tr- and ends in -auma, most of the goths had, you know, been through stuff. There was the accountant goth who had been raised by a drug-addicted mother. Another young woman who struggled with a recurrent eating disorder and lined her eyes with red powder, making her look like a nineteenth-century consumptive. The graphic designer whose father had committed suicide. And a melancholy musician who grew up in the Roman Catholic Church, his electronic compositions often reaching their apex in screams that sounded like a soul in the depths of doubt and despair.

Many of them were artists, and their lives reminded me of another artist, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, the 16th century painter famed for his depictions of religious figures as well as his numerous brawls. By the time he was 35, Caravaggio had already “slash[ed] the cloak of an adversary, scarr[ed] a guard,” and killed another man in a swordfight. His personal turbulence — a familiarity with the dark side of life — was legendary, and according to London’s National Gallery, he caused outrage by using “ordinary working people with irregular, rough and characterful faces as models for his saints.” A secretary in the Church of his time once described him as a “painter that can paint well, but of a dark spirit, and who has been for a lot of time far from God … and from any good thought.”

I remember attending an event at a different club with a girl I had a crush on, a red-haired Floridian who wore nothing but Melvins T-shirts and who was named, improbably, Barbie. Halfway through the night, we were astonished to see a strange substance on the tile dance floor — blood. Another attendee had stabbed himself in the stomach while dancing. “That’s so goth,” said a bystander, in reverent awe.

As I progressed in my gothic devotion I acquired accessories and household items. Upon returning home from work around 8 P.M., I would often turn on the fog machine in my bedroom, the same way one might use an essential oil diffuser or light a stick of incense. There I would sit in the darkness, the smoke billowing around me, as I contemplated the day that had passed.

“Ethereal goths” like myself wore long dresses. Rivetheads (those associated with industrial music like Skinny Puppy) wore chains and leather collars. And then there were the trench-coat-and-Oakleys goths whose look we called, unforgivably, “school shooter chic.” The spiritual identities of goths were as variegated as their fashions. Many did engage in a kind of worship of primordial forces such as the moon. But their sympathies with darker liminalities did not resemble the discouraging presence we Christians call “the Enemy,” the one who seeks to devour and destroy. There was an awareness of death not seen in contemporary culture. And a respect for both the brutality and the growth drive observed in wilderness. “Nature is Satan’s church,” I was told once by the director of a clothing store I worked at, a fellow who wore nothing but black draping tunics.

The political identities of the goths I knew were even more subterranean, and most found themselves outside the two-party consensus. In a widely viewed video of Bernie Sanders interviewing two mall goths in 1988, one can observe the same concerns that preoccupy anyone on the political periphery today — distrust in the integrity of our democracy, disgust with American imperialism, and dissatisfaction with free market supremacy. Bernie’s openness to these young people is notable. They are not articulate, but the anxiety they share about the economy as it has existed in our era — a sense of never being able to answer its demands, of somehow being ill-suited to the age — is deeply identifiable.

Remember not the sins of my youth, nor my transgressions. Psalm 25:7

I see now that my attraction to gothic culture was largely a desire for some kind of religious life. In the way that robes worn by monks and nuns symbolize death to the world, my choice to wear black was a renunciation of modern life and an expression of my need to live separate from it. My obsession with eroticism and the darker, more unwieldy contours of human sexuality was in fact a yearning for the Holy Spirit, for some kind of overwhelming, life-giving force to overtake me. My profound reverence for nature led me in part to my pro-life convictions.

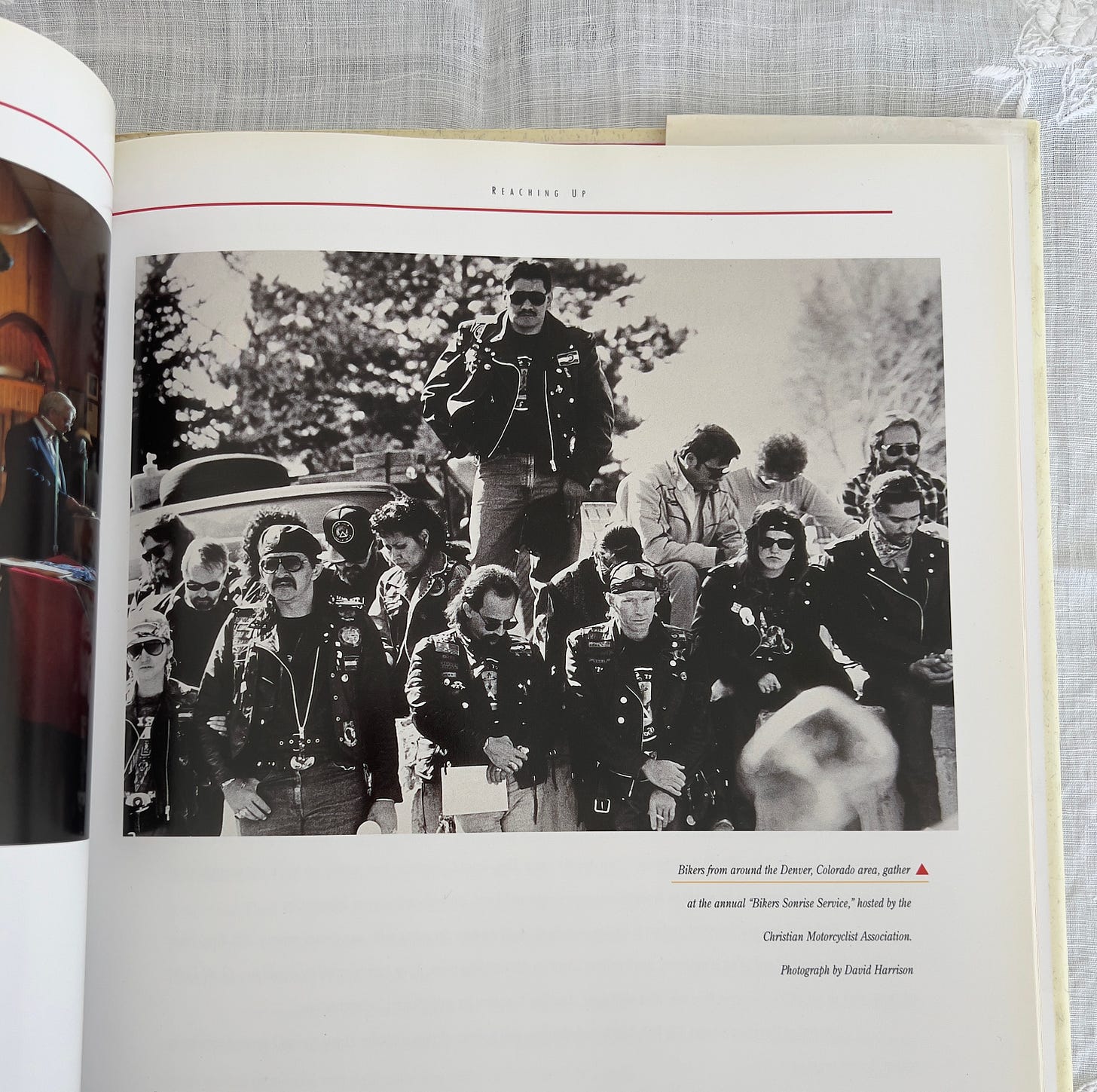

Several years ago, I was working in the respite house of a mental health non-profit. People with mental illness could come and stay there, for a few nights or a few weeks, as an alternative to psychiatric hospitalization. There, they could speak with peer counselors, attend support groups, or have private time to reflect and rest. On one afternoon I was walking upstairs when I spotted a woman in front of a doorway. She was about in her mid-50s, very butch, with a short spiky haircut. She explained to me that she was there because of her PTSD — she had been a first responder on 9/11 and ever since had suffered effects both physical and mental. As she spoke I glanced at her shirt, which had a picture of an eagle’s head and a long pathway toward a cross on a hill. “What’s that?” I said. She spun around and showed me the back of the shirt. “Christian Motorcylists Association,” she answered. “Instead of kickin’ people’s asses, we pray for ‘em.”

To say that in that moment my jaw dropped, and a whole new world opened up to me…

Instead of kicking people’s asses, we pray for them.

I now believe that you can be a badass, leather-wearing person, and prayer can be at the center of your life, rather than, you know, biting the heads off bats. When this woman spoke those words, I had already come back to the faith, but it opened a new level. I like my Christianity a little rough around the edges.