Advice to writers often centers on “playing the game.” How many bylines one should get in a year, where to pitch, what kind of day job you should have, how to contact editors, and how to deal with the consequences of the public nature of the calling.

That’s all well and good. But what is the point of writing? Furthermore, is the nature of writing truly public? In my mind, the acts of reading and writing are intensely private. Nothing could be more solitary or intimate than the connection between writer and reader, especially in today’s world of numbness and distraction. A reader is often on her phone, alone, in bed or on a train, when she engages with a text and hopes to find there something that will make the world make sense. Sometimes the only way I can write freely is if I can convince myself that the world is going to end tomorrow, and that I need not worry about paying rent, how I am going to survive, what will happen to my family, or what the damage to my reputation (if I ever had one) will be. If I can get into that mindset, I know I can tell my reader the truth. Sometimes having something to lose is the worst thing for a writer.

Charlotte Brontë was writing about love when she made Rochester say to Jane Eyre, “I sometimes have a [strange] feeling with regard to you — especially when you are near me, as now: it is as if I had a string somewhere under my left ribs, tightly and inextricably knotted to a similar string [in you].” The notion could apply just as exactly to the link between author and reader. If one can enter that space as a writer where worldly concerns cannot reach, then the feeling is precisely as Eyre describes: “I am not talking to you now through the medium of custom, conventionalities, nor even of mortal flesh: it is my spirit that addresses your spirit.”

Often, I do not even know the point of my writing, other than as a collection of vague impressions I feel I must communicate, because something in my heart tells me I need to. And so it is with three impressions I share today.

Marcel Proust once said that “the images selected by memory” are “arbitrary,” “narrow,” and “elusive.” I have often found that an aesthetic impression remains firmly in my memory, sometimes for years, until it can reemerge in some circumstance that elucidates its original meaning. One of such images was a photograph of an American teenager on a suburban street that appeared in The New York Times in the spring of 2007.

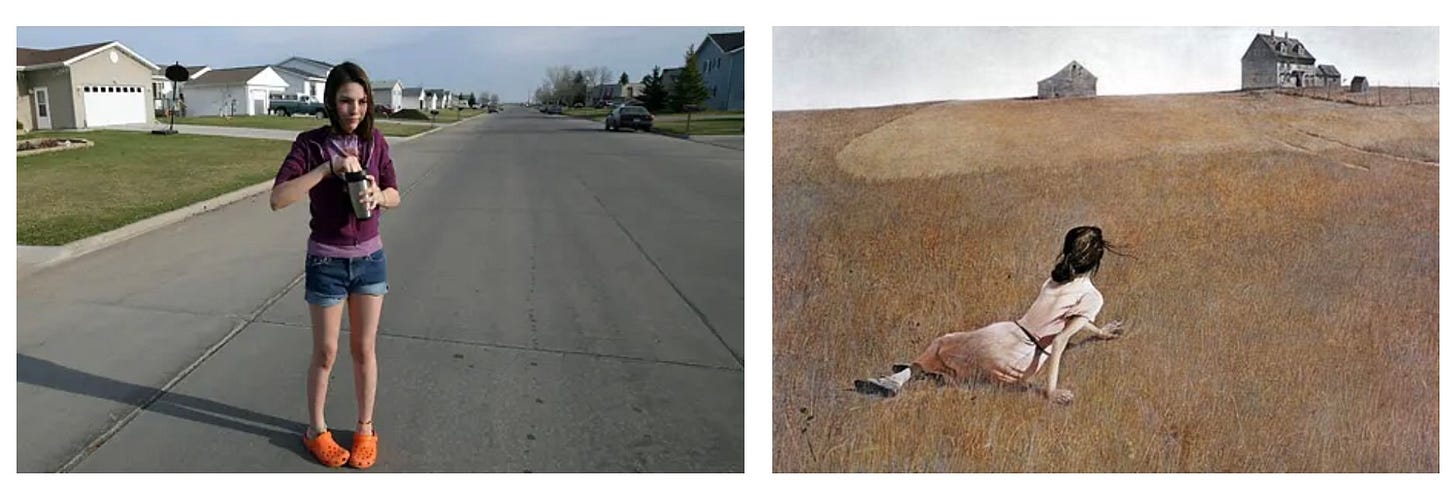

The image is of Anya Bailey, a girl growing up in Minnesota who was prescribed antipsychotics for an eating disorder. Starting around the age of twelve, “nothing tasted good to her,” her mother said, and a psychiatrist who in the surrounding years was paid more than $7,000 by drugmakers for lectures on their products gave her Risperdal, which achieved weight gain but led to a painful nerve disorder.

From the moment I saw it, this photograph has stayed in my mind, perhaps from a deep sense of identification but also because of aesthetic signifiers that did much more to explain Anya’s condition than anything in the article itself. One notices the sense of isolation — the empty street with all those houses looking exactly the same, the near total uniformity of the design. Her shadow behind her, dark and tall, serves as a visual representation of the subconscious that is the origin of her pain. Her bright orange shoes turn inward. She looks bewildered, as though lost or somehow numb, even though she is likely standing on the street where she grew up. The overwhelming impression is one of alienation and dissociation. The street stretches into the distance, and it is no wonder that this landscape cannot offer any solace or understanding to a young woman whose stirrings are clamped down as quickly as possible by the urge to conformity, the fear of her caretakers, and the ever-present pressure of financial reward.

Adolescence is a wilderness in which energies emerge that often lead to fear in girls and rage in boys. It has been posited that eating disorders are a response to the burgeoning of female sexuality; the erotic force within can feel so out of control that a young woman will do anything to stop its growth. In an environment which, as one can clearly see in the picture, provides no room for this wilderness — like a pot which cannot hold a blooming plant — it is no surprise that such unruliness and the fear it evokes would be met with a medical, rather than a spiritual, response. Another mother in the piece describes her then-seventeen-year old son, drugged on Seroquel and Abilify, as newly manageable. “I don’t have to worry about his rages; he’s appropriate; he’s pleasant to be around,” she told the reporters.

There is something about the image of Anya that reminds me of Andrew Wyeth’s famous painting “Christina’s World.” The same alienation is present; the same sense of simultaneous femininity and disablement. But whereas in the Wyeth painting one senses an inner striving, a desire or even a demand — an aspiration — the posture of the young woman on the left is blunted, disconnected, no longer seeking an answer.

After years of her daughter’s “constant discomfort” and “regular injections” to help with the nerve condition brought on by the antipsychotic, Anya’s mother finally expressed that “she wished she had waited to see whether counseling would help Anya before trying drugs.” The article concludes by saying that the young woman’s weight was now normal without the use of psychiatric interventions. What, then, catalyzed the precipitous use of heavy, detrimental medications in response to a common spiritual and emotional dilemma — the passage from one phase of life into another? Fear. “When things are dangerous, you use extraordinary measures,” said the doctor who had been involved in marketing lectures for the same pharmaceutical company that made Anya’s antipsychotic. The same fear that justified the loss of civil liberties after 9/11, that permitted authoritarian lockdowns against an illness that proved minimally risky to children and healthy adults, that now prompts parents to approve permanent physical alteration to their offspring lest they kill themselves. Panic can be employed to authorize almost any form of control. And although the medical professionals in the Times piece from 2007 swore their prescription choices were not influenced by speaking engagements for various pharmaceutical companies, the three reporters described “strong evidence that financial interests can affect decisions, often without people knowing it.”

The second impression I wish to share is a memory of driving in Columbia County, New York, sometime around the summer of 2015. In a landscape as ominous as it was serene, houses were few and far between as enormous fields of corn and soy stretched in front of my car. I stopped along the side of the road at a single wide home across from several fenced-in goats. Handmade signs proclaimed the sale of jam and cookies. A friendly elderly woman was waiting inside, and cheerfully packaged the preserves she had made herself as she chatted with me. Not a sound could be heard outside. I recognized that eerie silence from my childhood, when on a hot day the world rested and only the sun spoke. My communication with the older woman shifted when I mentioned how many dried and canned items she had on offer that could last for months, or even years. I spoke to her of my desire to move to the country, and her smile disappeared. “Something’s coming,” she said. I felt a chill on my arms.

I have thought of this woman’s words many times since that day. It would have been easy to dismiss such a phrase as the paranoia of an older rural resident, some kind of fever premonition of a murky and ill-defined persecution, or unannounced conflict. But she was right. Something did come: a pandemic, and a populist uprising which has changed the country irrevocably. My hair stood on end that day because I knew what she said to me. I knew it already.

Do we know things before they happen? Or do we dismiss them as vague anxieties, admonishing ourselves to not “overthink” and stamping out the clairvoyance of our senses with various suppressants? Carl Jung had a premonition of World War I in a series of dreams starting in 1913; in his autobiography he writes of being “suddenly seized by an overpowering vision” of mountains growing “higher and higher to protect our country … a frightful catastrophe was in progress.” Instead of pride in his foresight, Jung said he was “perplexed and nauseated, and ashamed of my weakness.”

As I wrote in an essay on pregnancy, which noted the strange apparition of pregnant models on runways in the years leading up to the fall of Roe, fashion can often act as a bellwether of a change that is coming, the flicker of something felt but not yet articulated. On January 22nd, 2020, Maison Margiela’s Spring Couture collection featured accessories that resembled the blue nitrile gloves that could be seen all over the streets of New York just two months later, worn by frightened citizens as the coronavirus infiltrated the city.

The third impression I wish to share is the memory of a Sofia Coppola film, “Marie Antoinette.” I remember seeing the film in 2006 when it came out, five years after 9/11 and less than two years before the financial crisis that would soon follow. I had admired Coppola’s work previously for what I deemed a specifically feminine perspective; her films were not plot or agenda-driven, but rather patient, intuitive meditations constructed of mood states. “Marie Antoinette” did not receive critical acclaim and was largely dismissed as a frivolity, but its effect on me was so profound as to remain in my consciousness all these years, especially its ending.

The film tracks the progression of the young female monarch from pre-coronation until the moment she must make her escape with her husband, the Dauphin, in a carriage by early morning light. Many scenes of accelerating extravagance have ensued; what begins as a penchant for tiny luxuries becomes an all-consuming fever for more and more consumption, more finery, more parties, more leisure, while an angry mob slowly collects in the distance. At one point the peasants encroach on the palace, dirty and starving. Marie bows her head at the balcony as a physical statement of contrition; but the gesture is not enough. It is too late, and the change has already arrived, even as the world still seems normal.

As their carriage makes its way across the paths of Versailles for the very last time, Marie’s husband asks her if she is admiring her grounds. Her eyes are red and her face is pale. “I’m saying goodbye,” she says.

The mystic Thomas Merton, an American monk and scholar, once wrote “A Prayer of Unknowing.” Addressing himself to the Almighty, he simply stated, “I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end.” Yet he also said that he would not be afraid, “for you are ever with me.”

I do not know what is coming. I do not know what lies ahead. I only know that something has ended. And although it may seem that things are back to normal, or soon may be, something has irrevocably shifted and the world we knew is gone.

Perhaps no secular society can really exist; a society must worship something, and if that something is not God, money will fill its place. A country whose financial towers reach higher than its houses of faith cannot stand forever.