I never had any hope of being politically correct.

I was raised in part by my great-grandmother, one Florence Simonds of Meco, New York, a tiny hamlet in the wilds of Fulton County.

She had been known in her youth as the fastest runner through a covered bridge; later in life, she worked as a glove stitcher and made 17 pies per day at a local hotel.

At some point, maybe when I was around nine years old, I started recording her speech by hand in a notebook.

I distinctly remember one occasion, on which a group of us was gathered to eat at the now-defunct Ponderosa Steakhouse in Johnstown, New York, shortly after I had begun this practice.

Various members of the family murmured how hungry they were as the waitress approached with the food.

“I could eat a pig with the shit right on it,” Florence said.

“Is there anything else you need?” The waitress sweetly asked the table.

“Just get out of here and leave us alone,” was Florence’s gruff response.

She called members of her community she deemed mentally slow either a “dimwit” or a “half-bake.” She, or one of her sisters, once responded to news of a long-awaited pregnancy with the retort, “We don’t talk about that hind end stuff.” Even more elegant was the way she often announced her need to urinate: “I gotta wet.”

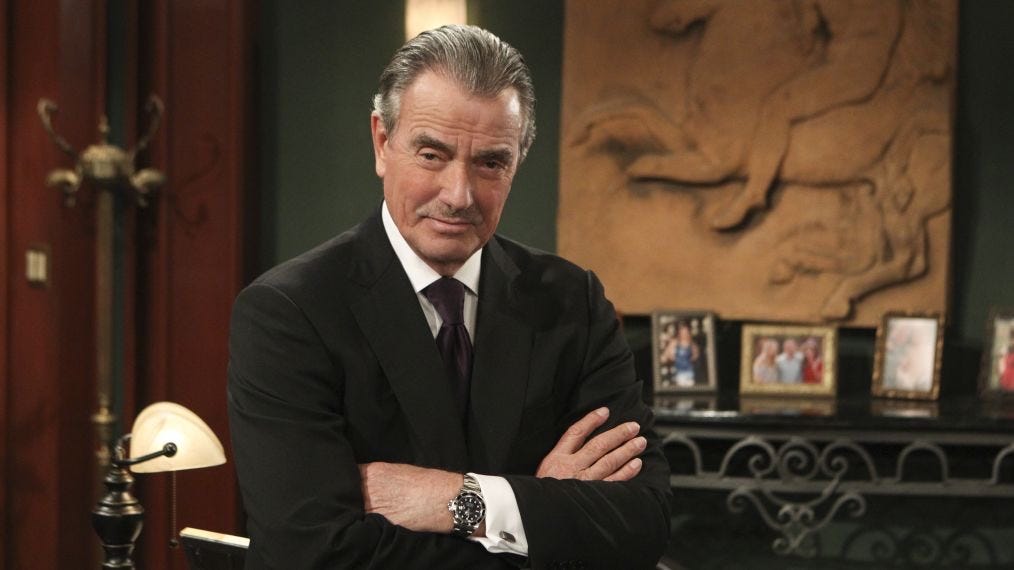

Her favorite soap opera was “The Young and the Restless,” and many were the lunchtimes I spent with her on the couch (which she called the Davenport), while she sat in a well-worn BarcaLounger with a doily on top, shouting back at the TV.

“Answer that man, hussy! I could rip her eyes out.” These interjections were punctuated by belches. “That one looks like the one that chased Clinton. Shut your face, y’old slop. Looks like an old hound dog with that hairdo. She’s sneakin’ up on him. Watch her! Watch her! She’s after you, you fool! She’s set her cap on him. Ain’t he a sucker? It’s not over. Liar. LIAR!!! He ain’t got it settled at all. See? Here’s her lawyer.”

The program usually proceeded uninterrupted, unless there was content of a sexual nature. The moment two characters kissed, or a lustful glance appeared in someone’e eye, she would shuffle across the room in her terry cloth slippers, muttering in a low, guttural tone: “DIRTY ROTTEN FILTH. DIRTY ROTTEN SMUT,” and turn the TV off with great flair. Then, after several moments had passed and the danger had abated, she’d switch it on again and shuffle back to her seat.

These lunchtimes were always characterized by the same delicious meal: a turkey sandwich with Hellmann’s and iceberg lettuce, Campbell’s soup with star-shaped noodles, and ginger ale. And every day, as soon as the program ended, the phone would ring with a request for post-show analysis. It was her sister, Abbie, seeking to debrief on the episode and the travails of its male lead, Victor.

Florence answered the phone, no matter who was calling, with a nonverbal utterance I can only spell as “YUT.” And often, she would end the conversation just as unceremoniously, saying something like, “Wellt, I gotta put a girdle on.”

At that point, the main event of the day concluded, I set off into the vast fields behind Florence’s house, where even at eight or nine years old I was allowed to roam completely free and unaccompanied. After a brief, winding path through the woods which my father worked hard to maintain, and a momentarily hazardous duck under the rusting electric fence, I could walk for hours on the great expanse of a neighboring farmer’s land.

It always seemed to me that this land represented the kingdom of heaven, and my great-grandmother, despite or because of her candor among many other qualities, exactly the kind of woman of God I’d one day aspire to be.

She brought me with her to church every Sunday, during those summers I would spend weeks at her house. Sometimes the pastor came over to talk through an issue in the family. And we made pies. Many, many pies. Just below the countertop where she taught me how to use a rolling pin and make a thumb-indentation along the crust hung a wooden cross with the carved words: “Keep Looking Up.” We picked blackberries from the bushes on the side of her lawn. I observed her every action throughout the day, from when she powdered herself after a shower to when she slathered herself in Vicks VapoRub at night. Sometimes I slept beside her in the grand bed in her master bedroom, and sometimes in the adjacent room across the hall.

I always felt that before I existed, my soul was already present in the fields behind her house, and that my parents, by making love to each other, called it down to Earth. Maybe that is why I felt so at home there. I also remember my father saying that when Florence died, her spirit would always be in those fields.

“Don’t forget, no one can help you like God. He is always there,” she wrote to me in a letter when I was fourteen, sometime after my family had moved to a different state. But I did forget, and for many years lived in a state of anxiety, distress, and mistrust, before coming back to the faith I hold so close.

Michel de Montaigne, in his famous essay about the riding accident which led to a near-death experience, said that “it is not without reason that we are taught to consider sleep as a resemblance of death.” This thought came to me many times in the early days of the coronavirus in New York City, then the epicenter. I remember passing entire days inside the apartment alone, and that at times my solitude was so encompassing that I entered into a state of dizziness. When I lay in bed at night, I often wondered if the shortness of breath that would come to me in fear and panic was close to what thousands of Covid patients around me were feeling as they died, intubated. Montaigne suggests that what we feel upon death is not pain, but rather “pleasure in languishing and letting [one]self go” — “that sweetness that people feel when they glide into a slumber.” It was in these moments, after I had spent the day looking at the corpse truck parked at the public hospital across the street, that the thought of my great-grandmother would come to me.

She often tucked me in at night when I stayed with her, and the last thing I’d remember before sleeping was her benevolent face above me. The next morning she’d remark, exactly the same each day, that I had gone “out like a light.” This is what I imagine death will feel like: not a panic, not a shortness of respiration, but a welcome by God — an embrace.