In the 1991 academic title “Feminism Confronts Technology,” scholar Judy Wajcman writes that in the last quarter of the twentieth century, a form of feminism emerged which “exalted femininity for its own sake.” Its writers emphasized what they viewed as innate sex differences and “celebrate[d]” the “specifically feminine.” Some of them “abandoned the idea that what was ‘specifically feminine’ was socially produced,” and claimed that certain aspects of femininity are “ineradicable.” She also mentions a philosophical mode called “romantic-conservatism:” an “anti-atomistic style of thinking which advocates holism, organic unity, and the qualitative rather than the quantitative as the preferred style of thought.”

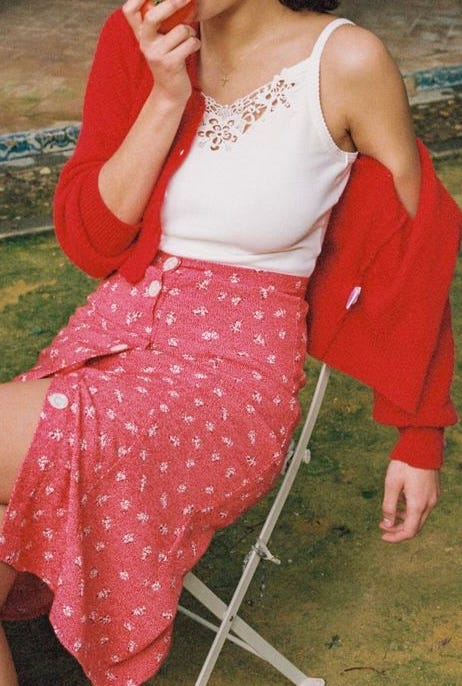

One can see aesthetic glimmers of these tendencies in the female fashions of the past several years. Beginning with the return of the corset in the late 2010’s, the last several seasons have produced a preponderance of microtrends which champion the impractically girlish, the indulgently sensual, and present in some subtle way a resistance to recent technological developments, even as they are shared by technological means. Designers such as Simone Rocha and Sandy Liang have taken part in the huge bow trend which has now lasted several seasons, much to the annoyance of those who favor more “grown-up” style. A TikTok trend from last summer called “Tomato Girl” expressed itself though oranges, reds, and vermilions, as millions of women posted and reposted pictures of themselves slicing vegetables, sitting in the sun, and painting freckles on their cheeks. The “coquette” trend also shows no signs of abating, as Kendall Jenner, the highest-paid model for six years and counting, displayed when she posed on Instagram in a white Rodarte gown with black bows on the shoulders. Roses are now in fashion and can be seen adorning hair and drawn into patterns on camisoles and cardigans (as in the new indie label Rosette). After decades of power dressing, in which a woman emulates a male silhouette, and athleisure, in which the outfit is “optimized” to facilitate a streamlined, efficient lifestyle, fashion is “embracing hyperfemininity,” writes Highsnobiety’s Alexandra Pauly.

What is the rose trend about? It’s “a reclamation of girlhood and womanhood that flies in the face of the messaging many Millennials and Gen Z’ers grew up with: that being ‘too’ girly is undesirable,” or that it’s “an affront to feminism,” Pauly explains. She interviews a floral designer who proffers that roses have entered the chat because “we are in need of connection, a return to romance,” and “healing.” The plant has long been used as a medicine for ailments both physical and spiritual. In 1991, the same year that “Feminism Confronts Technology” was written, authors Susan Curtis and Romy Fraser wrote in their encyclopedic “Natural Healing for Women” that rose petals should be added to tea “where there is an emotional aspect to a problem, and feelings of holding back.” Roses connote connection. It’s a craving Pauly claims is “coming to a head amid the crush of disembodied, digital communication that social media, online dating, and remote work requires.” A punk band of today might call itself Roses Against Remote Work instead of Rage Against the Machine.

As certain progressive circles approached the end of the last decade and hyper-political correctness started sinking its claws into casual conversation, it became verboten to call young adult women “girls” (as in “that girl I know”), because this was seen as infantilization. It’s hard not to see every ribbon, floral accessory, and crimson sundress as an (eminently feminine) middle finger to that notion. On a deeper level, the bow may represent a reclamation of chastity, or even celibacy. Bows and ribbons, both seductive and protective, must be intentionally undone before consumption. They contain or bind something of value.

Famed fashion critic Valerie Steele defended classic feminine shapewear in “The Corset: A Cultural History” when she wrote that “once women no longer felt that they had to wear corsets — when the corset, in fact, was stigmatized — some women consciously chose to wear them.” In a more recent conversation she added that “women wore corsets for more than 400 years because they saw some value in the corset for themselves.” She says the idea that women wore garments like corsets merely for reasons of societal imposition is excessively “simplified.” The nu-corset trend that appeared in the middle of the last decade was a seed that led to the flowering of bows, ribbons, and fruit-inspired fashion we see now. Only in the last month, a new blush aesthetic has emerged: gone is the harsh contouring of years past, and a flushed, romantic rouge is predominant.

The mainstream fashion press seems perplexed by this shift. Elle says “it’s not a moment, it’s a movement.” And The New York Times complains that for now, “we’re stuck” with constant reiterations of the hyper-femme. It is possible that some may have hoped for an “End of History”-style End of Femininity once women had reached a certain point in the economic hierarchy. That does not appear to be happening. The perennial quality of women’s attraction to feminine fashion suggests that there is something innate and instinctual in these aesthetic choices. It should be exalted rather than sneered at.