I visited Kentucky in July, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking of it since. Growing up in the Northeast, it was a place I never considered or heard spoken of, unless it was someone ignorantly laughing over the landlocked states. If Ohio is the nation’s heart, Kentucky may as well have been its armpit. Once my family left upstate New York and settled in Massachusetts, we were in a town where people considered the flyover states some kind of no man’s land.

Imagine my fascination, then, when I discovered that not only is Kentucky incredibly beautiful and filled with kind, plucky people, but that it is suffused with a spiritual energy that left a profound impression.

As soon as the plane landed at SDF, I knew I was in a place where people still go to church because even the airport convenience shops had coasters and keychains with Jesus-speak on them. The monk who picked me up, although he was not wearing a habit, resembled a prophet because of his long white beard. As we traveled on the highway toward the monastery he told me that there are three counties — Nelson, Washington, and Marion — that are known as the Holy Land of Kentucky. These counties have been home to hundreds of Catholic families since the late eighteenth century, and many of their descendants still live there. It was common to see a certain kind of modest, one-story home along the road as we progressed, with a pickup truck in the driveway and a Blessed Mother statue on the lawn.

I later found out through watching a historical film that this constellation of counties was “the first place that Catholics came in any great numbers off the East Coast,” and that in fact “Kentucky was the first Western star on the American flag … this was the first Western land of the new nation.” The documentary explains that “when they came here, they were part of a great Westward motion. And they were really part of something you might call cosmic … a movement also to something new in American life … they were part of that American spirit as well as the Catholic spirit.”

In Kentucky, which is slightly Midwestern and more than slightly Southern, there is a ring-shaped region called The Knobs where this frontier Catholicism began to take shape. “Knobs” are small hills, more diminutive than mountains yet big enough to give the landscape its characteristic roll. The ring of knobs surrounds the Bluegrass, which includes the city of Lexington. Beneath this is an area called Pennyroyal, or the Mississippi Plateau. And two hours south is Nashville, the home of country music and the cultural jewel of Tennessee.

A woman I met on my travels, when I shared that I lived in Washington, remarked: “Bet that’s a shitshow!” And when I complimented her intoxicating drawl, she fired back: “Ah don’t have an accent, YEW have an accent!” (Apologies for my illustrative spelling.) It seemed to me that she carried the same gumption that the historian in the documentary attributed to the early Catholic pioneers, calling them “pious and funny and kind.” I also learned that Kentucky is thought of as a spirited place not only for its religious history, but because of one of its main exports: bourbon. Even the monks at Gethsemani Abbey made chocolate fudge infused with the local barrel-aged whiskey. One evening after the pre-dinner prayer, known as Vespers, a small plate appeared in the dining area with dozens of fudge squares pierced by toothpicks.

The license plates of Kentucky often include the phrases “In God We Trust” and “Unbridled Spirit” — referring to the state’s long association with horses. The first Catholic church building was established in 1792, in a town called Holy Cross. An original group of worshippers had come from Maryland in 1785, seeking “a better life” and “good farmland.” Most of the American South is Baptist or nondenominational, but this location “is a very unusual part of the country,” the documentary explains. “As you come south of the Ohio River, there are very few rural areas that are Catholic in America … with the exception,” it notes, “of the Kentucky Holy Land.”

The state has been touched throughout the centuries by other spiritual phenomena, most notably the Second Great Awakening in 1801. Part of a series of rapturous gatherings that swept through American society, the revival at Cane Ridge developed into a crowd of 20,000 people set aflame by the Holy Spirit. It began as a Presbyterian communion service and exploded into something supernatural when a woman attendee began to shout and sing. Before long, thousands were praying with great fervor, falling backwards in a movement known as being “slain in the Spirit.” A Methodist named John McGee remembered that he “went through the house shouting and exhorting with all possible ecstasy and energy, and the floor was soon covered with the slain.” It is estimated that between 1,000 and 3,000 people were converted that week.

In the Spring of 2023, a similar event happened in Wilmore, Kentucky at a Christian university named for evangelist Francis Asbury. It became known as the Asbury Awakening. On the morning of February 8th, a customary student worship service shifted when one young man got up and began to talk about his defects. By that evening, a revival was happening, with hundreds of people flooding the auditorium. It developed into a sixteen-day event drawing tens of thousands. Student body president Alison Perfater spoke about the experience, saying that “there is a young army of believers who are rising to claim Christianity, the faith, as their own, as a young generation and as a free generation.” Noting that the university switchboard was receiving an outpouring of calls and that visitors had arrived from almost every state and several foreign countries, she proclaimed that “the Holy Spirit has interceded for us.” In countless interviews from that time, students talked about spontaneous healings, solidarity among former enemies, praying for those in recovery, overcoming mental health issues, and rejecting the narratives of despair that had been fed to them by older generations and the secular culture.

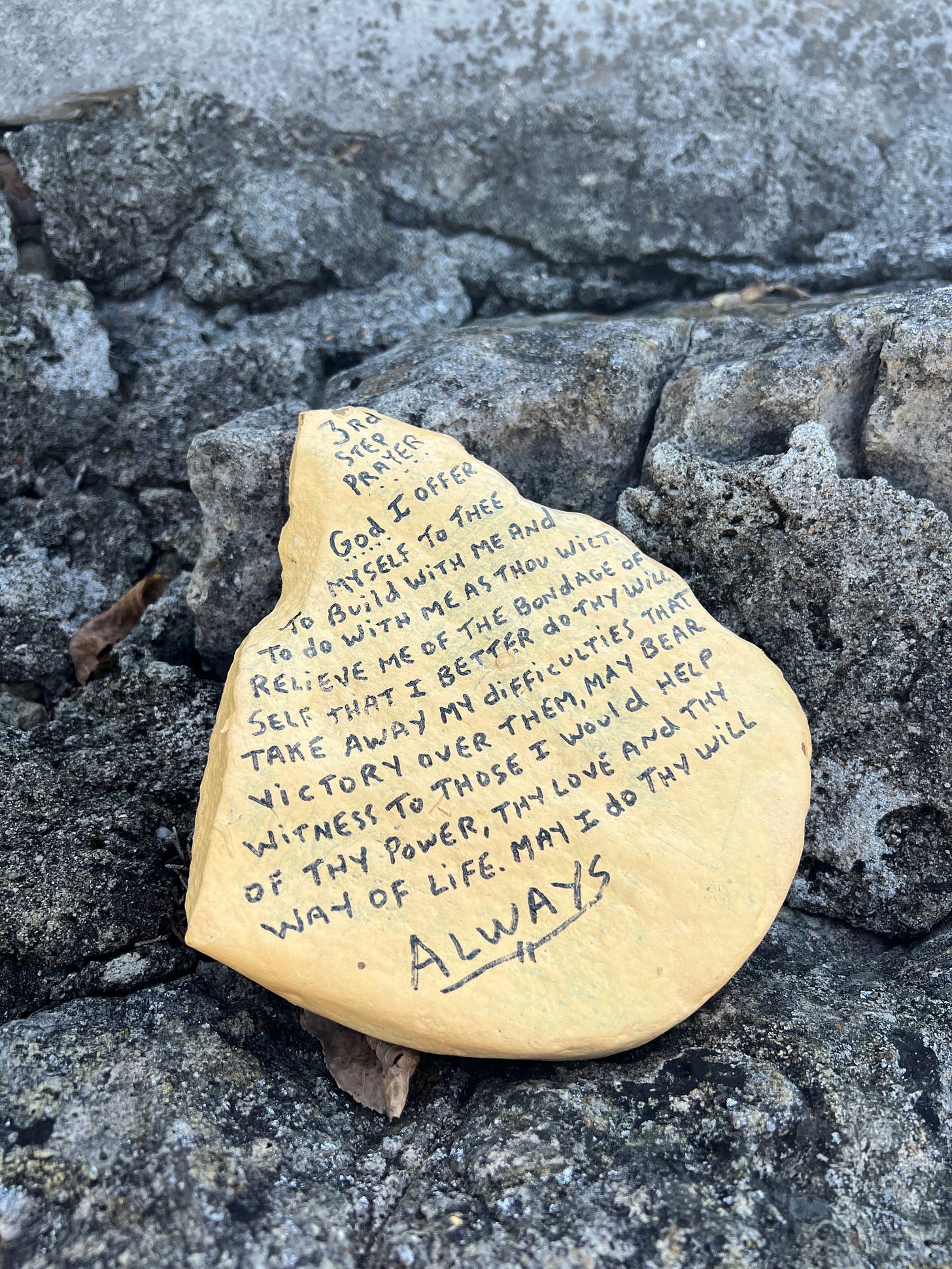

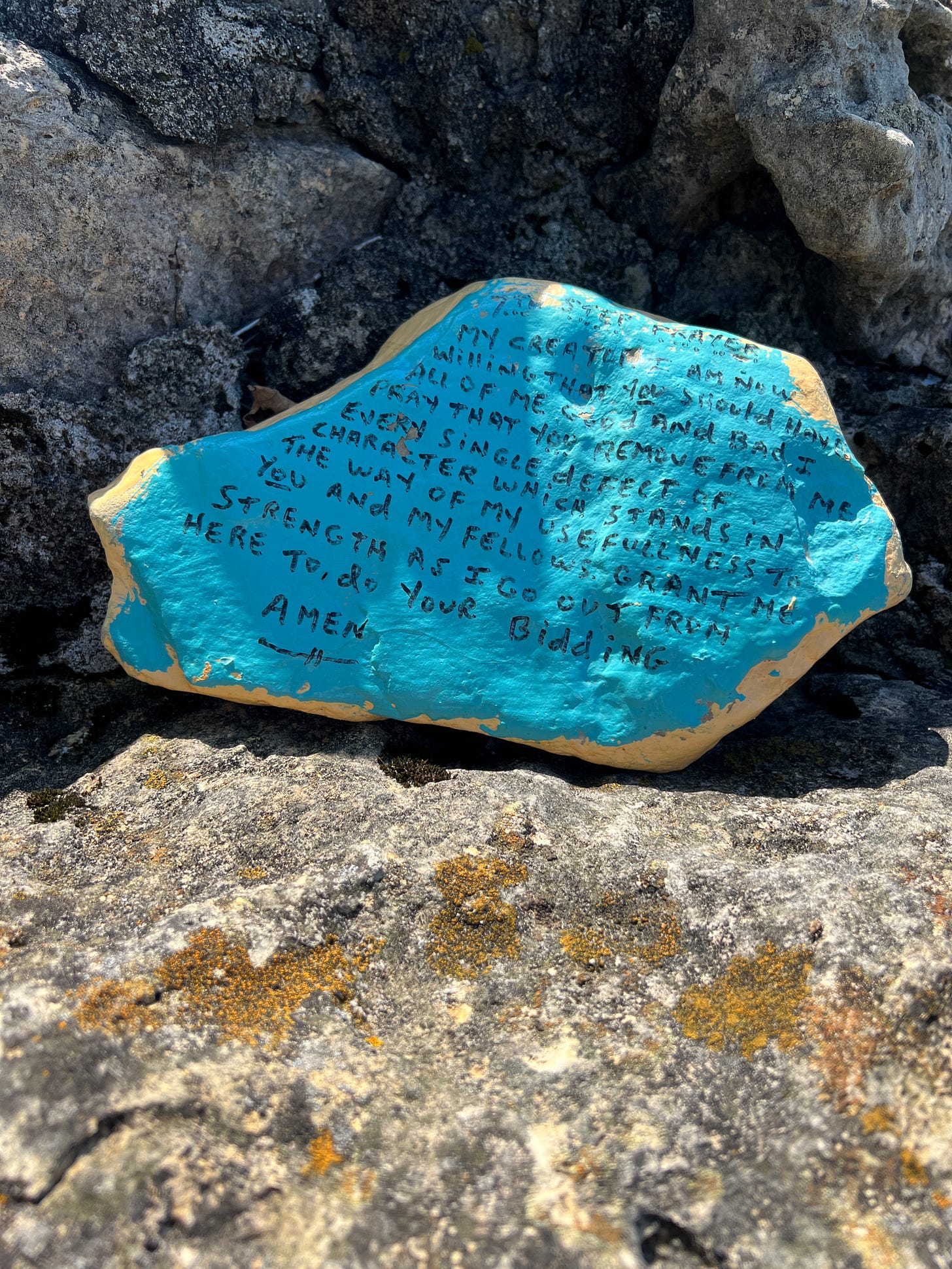

The final Step of the Twelve Steps of Recovery, beginning initially with Alcoholics Anonymous but now existing in a variety of programs that address everything from drug use to family problems, states that “having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these Steps, we tried to carry this message to others and to practice these principles in all our affairs.” It was evident to me at Gethsemani that many people in recovery had been there. The bookstore, in addition to selections on Christian mysticism and the saints, offered several prayer books on healing from addiction and other debilitating behaviors. When I went outside one hot afternoon and walked through the grass to a stone cross mounted on a hill, I saw handmade objects left behind by other retreatants. Among them were the 3rd Step Prayer1 and the 7th Step Prayer.2

Kentucky may be overlooked by people on the coasts or others who have never been there, but it has definitely been touched by the hand of God. It is said that the state’s name originates from an Iroquois word meaning “meadowland” or a Wyandot word meaning “land of tomorrow.” There is something very specific about the way the clouds hang in the sky in Kentucky. It’s as if they have been pinned directly by God’s hand, rather than just floating by. Walking through those fields, I felt that I had found something I had been seeking for a very long time: an America I recognized, that stretched out limitless before me, infinite and full of possibility.

Ross Douthat wrote a column last year in which he expressed that despite the cynical minimization by atheistic thinkers of our national propensity for religion, and despite even the cajoling and plotting of various evangelists and theologians, the true reignition of American Christianity may already be “happening in some obscure place” or in the heart of “some obscure individual, in whose visions an entirely unexpected future might be taking shape.”

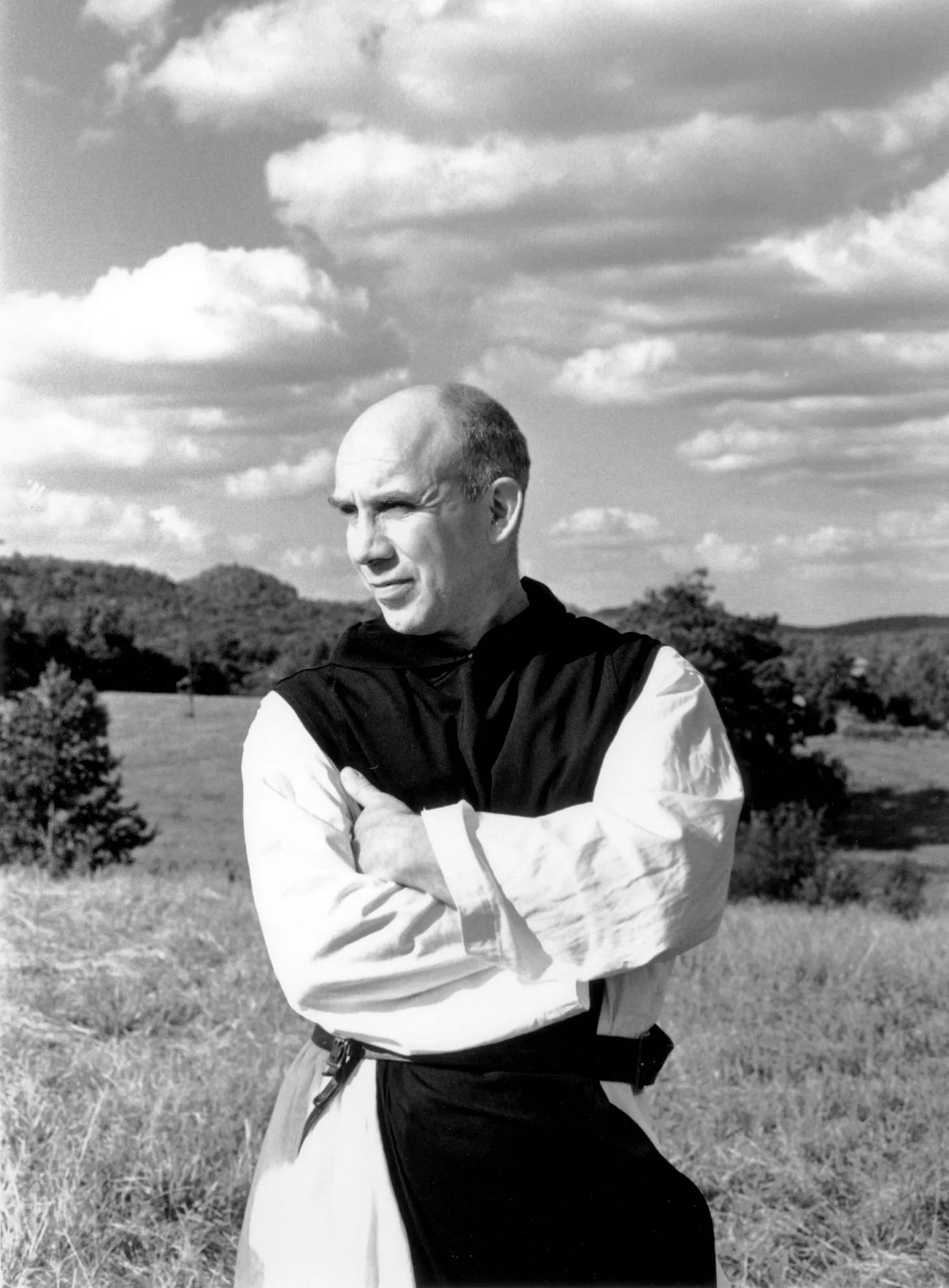

Thomas Merton, a monk who lived at Gethsemani Abbey in the twentieth century, had once been a brilliant academic with a future in teaching and writing at various institutions in the North. Some of his friends and former teachers thought he was wasting his life and his talent when he entered the silent monastery in Kentucky’s countryside. But the first time he witnessed the liturgy at what would become his home, he knew something. “This church,” he wrote seven years later, “is the real capital of the country in which we are living. This is the center of all the vitality that is in America. This is the cause and reason why the nation is holding together.” And the people praying therein, he said, “are doing for their land what no army, no congress, no president could ever do as such: they are winning for it the grace and the protection and the friendship of God.”

God, I offer myself to Thee — to build with me and to do with me as Thou wilt. Relieve me of the bondage of self, that I may better do Thy will. Take away my difficulties, that victory over them may bear witness to those I would help of Thy Power, Thy Love, and Thy Way of life. May I do Thy will always!

My Creator, I am now willing that you should have all of me, good and bad. I pray that you now remove from me every single defect of character which stands in the way of my usefulness to you and my fellows. Grant me strength, as I go out from here, to do your bidding. Amen.