My great religion is a belief in the blood, the flesh, as being wiser than the intellect. —D.H. Lawrence

There has been much talk of Romanticism. There has been much talk of contemporary industrial revolution. There has been much talk of going offline.

In 2023, critic Ted Gioia wrote an essay on Substack called “Notes Toward a New Romanticism.” The novelist Ross Barkan expanded on Gioia’s ideas in breathless commentaries for The Guardian and his own Substack. Intellectual project Wisdom of Crowds rounded up examples of similar assertions in February. And of course, the new Catholic pope, Leo XIV, explained his choice of name as honoring Pope Leo XIII, who sought to defend humanity and human values from the brutishness of the factory age. In an address to the College of Cardinals on May 10th, the new pontiff invoked the need for a “response to another industrial revolution and to developments in the field of artificial intelligence.”

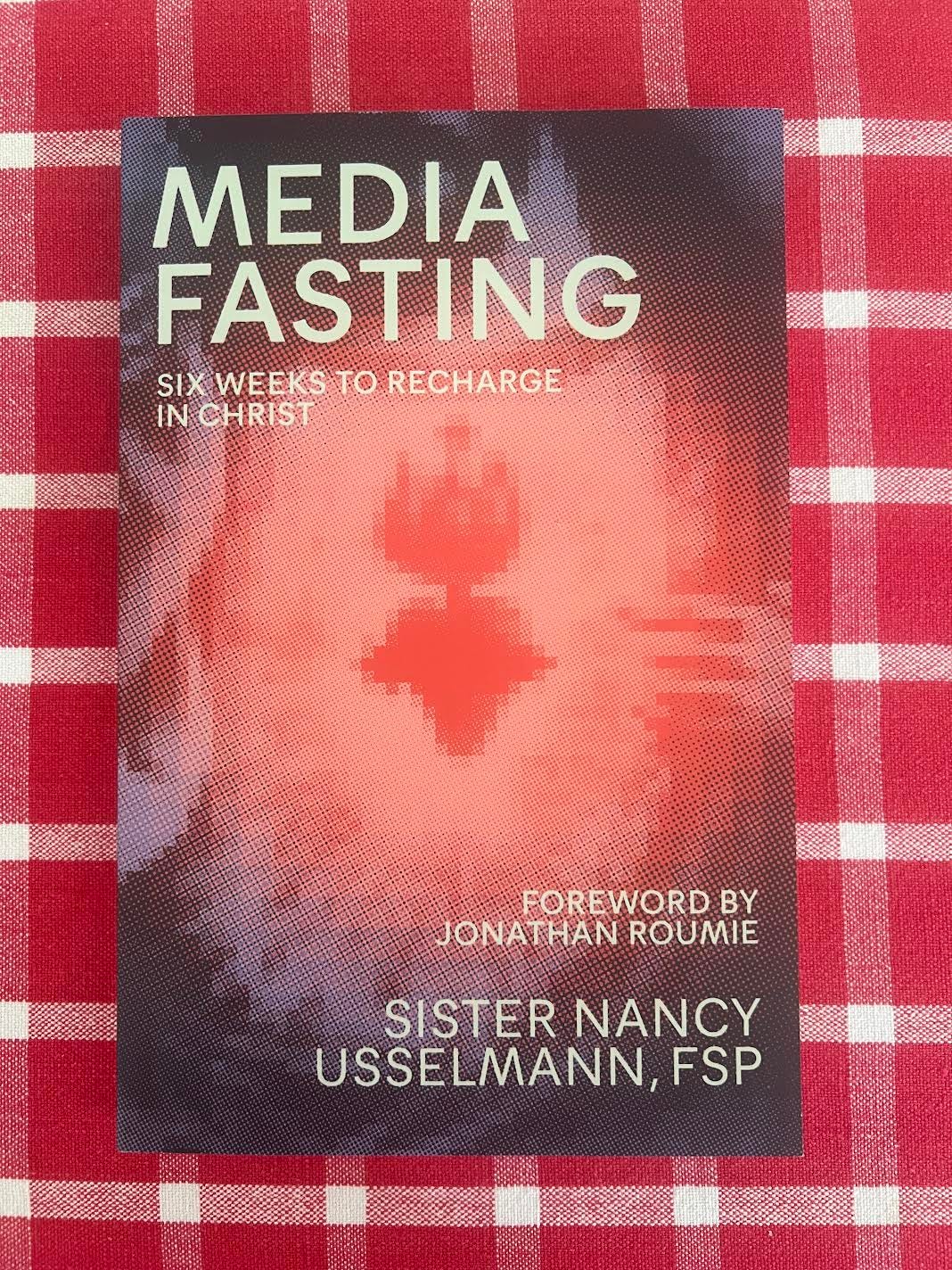

There are growing movements whose aim is to release human beings from unnecessary bondage to the internet. Most of these initiatives do not carry the reactionary impulse their critics ascribe to them, because they acknowledge the irreversible presence of the internet and its valid uses. They do, however, emphasize relinquishing the spirit of addiction that being too online can bring about. A new book by Pauline Sister Nancy Usselmann, called Media Fasting: Six Weeks to Recharge in Christ, presents the benefits of reducing phone and internet use and provides structured plans. A fledgling recovery fellowship, Internet and Technology Addicts Anonymous, is increasing in members and offers multiple meetings every day (they maintain that even online meetings are a “resource that ultimately helps us spend less time on the screen”). A mysterious group called Offline DC, whose posters I have seen pasted in my neighborhood, describes itself as “an experimental community education project” that exhorts people to participate in a “Month Offline.”

Five months ago, I felt called to move in a similar direction. I wanted to see how radically offline I could be while still maintaining responsibility to the work I needed to do, the bills I needed to pay, and the appointments I needed to keep. I aimed to create a Walden in my mind.

Henry David Thoreau:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.

For four months, I got up at 6:30 and did not go online until 10:00. I signed out each evening at 5:30PM. I spent the rest of the night reading. I did not look at my phone if I woke up in the middle of the night. I did not use internet at all on Sundays.

What did I read? D.H. Lawrence, of course. I returned to one of my favorite books of all time: Lady Chatterley’s Lover. I found that it spoke prophetically of our time, more prophetically perhaps than the graceful husks of the original Romantic poets.

And what a joy it was to read! To read books — to hold them in my hands, in the cool of the Spring evening — to breathe in their scent (of either fresh ink, in a new book, or the musty smell of a barn in a used book). To turn each page in peace, without scrolling, without having to ingest the retorts of a million dicks in the comment section. To experience the peace, the pure peace of that author’s creation, without needing to imbibe every contrary argument or petty objection immediately afterward. As time went on, my capacity to read long passages was restored, and the book spoke to me as profoundly as it did the first time I read it, at 19.

Lawrence’s early description of the life of Constance, a healthy woman married to an aristocratic invalid, who eventually falls in love with her husband’s roughhewn gamekeeper:

There was no touch, no actual contact … of physical life they lived very little.

Later:

Her body was going meaningless, going full and opaque, so much insignificant substance. It made her feel immensely depressed and hopeless … The mental life! Suddenly she hated it with a rushing fury … The sense of deep physical injustice burned her to her very soul.

When she speaks to her husband of the workers in his charge, she characterizes their lives as “industrialized and hopeless, and so are ours.” She hears one of his faux-intellectual comrades invoke the phrase “resurrection of the body” in a cavalier fashion, and it sticks with her.

She didn’t at all know what it meant, but it comforted her, as meaningless things may do.

When she is walking through the woods, soon to be healed by her illicit affair with her husband’s servant, the words come back to her.

I believe in the resurrection of the body! … In the wind of March endless phrases swept through her consciousness.

As Constance’s body awakens, Lawrence’s descriptions of nature grow ever more intense.

Connie went to the wood directly after lunch. It was really a lovely day, the first dandelions making suns, the first daisies so white. The hazel thicket was a lacework of half-open leaves, and the last dusty perpendicular of the catkins. Yellow celandines were now in crowds, flat open, pressed back in urgency, and the yellow glitter of themselves. It was the yellow, the powerful yellow of early summer. And primroses were broad, and full of pale abandon, thick-clustered primroses no longer shy. The lush, dark green of hyacinths was a sea, with buds rising like pale corn, while in the riding the forget-me-nots were fluffing up, and columbines were unfolding their ink-purple riches, and there were bits of blue bird’s eggshell under a bush. Everywhere the bud-knots and the leap of life!

… Everything was serene, brown chickens running lustily. Connie walked on towards the cottage, because she wanted to find [the gamekeeper].

Her lover spouts off about industrialization himself, how society is trending toward

“killing off the human thing, and worshipping the mechanical thing … Pay money, money, money to them that will take the spunk out of mankind, and leave ‘em all little twiddling machines.”

And then:

“Sex is really only touch, the closest of all touch. And it’s touch we’re afraid of. We’re only half-conscious, and half alive. We’ve got to come alive and aware.”

Constance, in a contentious conversation with her husband, finally exclaims:

“Give me the body. I believe the life of the body is a greater reality than the life of the mind: when the body is really awakened to life. But so many people … have only got minds tacked on to their physical corpses … The human body is only just coming to real life … it is really rising from the tomb. And it will be a lovely, lovely life in the lovely universe, the life of the human body.”

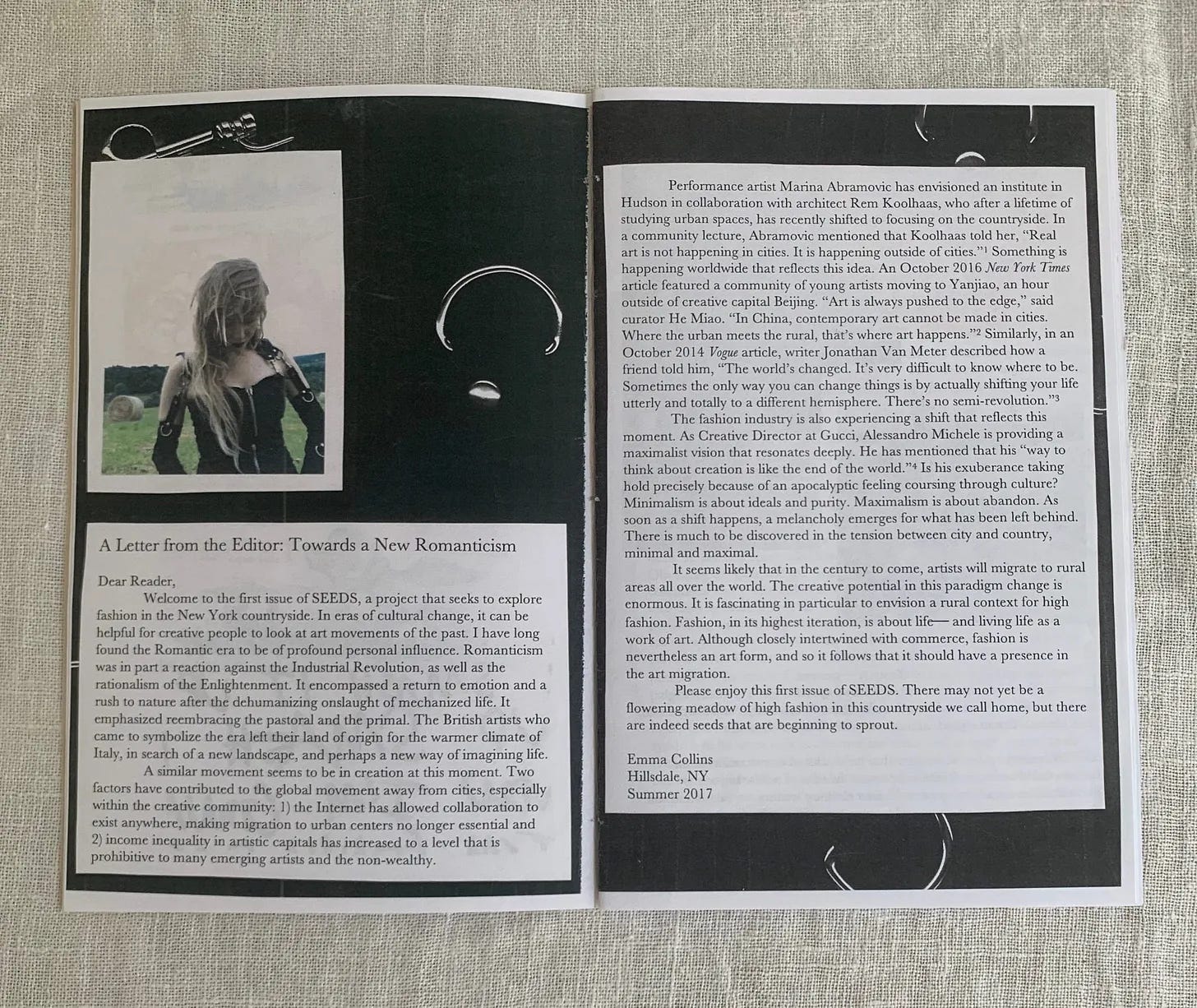

Let it be known that in the Summer of 2017, when I was living in upstate New York, I made a zine that investigated growing art movements in rural areas. It was my belief that the internet would enable young artists to establish communities in non-urban areas, and that rural life was indeed the frontier of artistic creation. My editor’s note was entitled “Towards a New Romanticism.”

What I am about to say may also be prescient: I no longer believe Romanticism is enough. We may need some kind of neo-Romantic movement, but what we really need is a return to Embodiment. We need a physical reawakening. The body is the key to our era.

The Romantic philosophers and poets of the late 18th and early 19th centuries were responding to the sensed illegitimacy or loss in resonance of orthodox religious orders. That is what the Enlightenment had taken from them.

But the Internet is taking something different from us. It is taking our connection to our bodies. Therefore, in the way that the Romantic impulse conveyed a need to reestablish contact with an Ethereal Beyond, a potential Embodiment movement will establish a new conception of what it means to exist in the physical — to have flesh — to incarnate.

To be excessively online is to participate in one’s own excarnation.

I was convinced of a back-to-the-land movement ten years ago. Now I am convinced of a back-to-the-body movement.

The Saints of this movement are D.H. Lawrence and Colette. Its sacred text is The Theology of the Body by John Paul II.

This movement will have its enemies and detractors. Of the most facile kind are counter-statements such as these:

A masterclass in the slothful cool-girl eyeroll, this genre of utterance was ruthlessly (and majestically) pilloried by Katie Roiphe in a 2011 Slate essay. Reacting to a Gawker post that had ridiculed her work, she perfectly characterized the website and all its rhetorical descendants:

It’s all tone, no content, and the tone itself is monotonously unvaried—namely the sneer. (Of course, fans and devotees of Gawker might argue that I am exaggerating and there is a full, impressive range of tone that goes all the way from smirk to sneer.) What the Gawker ethos (i.e., the sneer) comes down to is this: Everyone is a phony.

She continues:

They once republished a piece about one of my essays: “I think she wrote the piece because she liked the idea of having a big, long, ‘provocative’ think piece in the NYTBR, one lots of people would argue about. I don’t blame her for that. If I had my shit more together, I’d probably aim for the same brass ring of neediness.” In other words, they murmur to their reader: I am brilliant and talented, but too cool or sublimely untainted by anything as sordid and uninteresting as the ambition to try to do anything.

Roiphe comes to the meat of her argument:

Of course one could argue that Gawker is less the real scourge than the gawkerish habits of mind that have been internalized by certain segments of the Internet-scouring populace. To casually and sloppily take down, to ironize, to sneer comes very naturally to us, we can do it in our sleep, but to care, to try, to want, are harder. And to admit that you care or are trying or are wanting, well, forget it: Those will be impossible.

To succumb to the demands of the internet, without critique or discernment, or the exercising of one’s will in choosing wellbeing over addiction, is indeed to be a mollusk. Mollusks have shells for a reason. In their softness and vulnerability, they need protection. And we too need protection from the mechanistic advancements that are occurring.

In the pamphlet Finding a Spiritual Path Through an Addictive Culture, Catholic priest Raymond F. Dlugos of the Order of Saint Augustine (the same order that Pope Leo belongs to) characterizes an addictive culture as one which

continually reinforces destructive choices while ignoring or even punishing choices that might lead to a better life, love, and goodness. An addictive culture is one that has lost its freedom, perhaps even as it celebrates its freedom to function in a self-destructive way.

But he reassures us:

We also need to trust that we do have the capability to make choices for freedom and health, even within the pervasive influence of an addictive culture … While it is not likely that we can make the choice for freedom and health all at once, we can make one choice at a time. Each time we find ourselves being swept toward the addictive path by its powerful force and choose instead another direction, we are choosing life rather than death.

These thoughts are perhaps a preface to what I wanted to share with my readers: I have determined that my Substack works best when not connected to the payment processor. The reasons for this are several.

There are times when, due to other commitments or health-related reasons, I need to post with greater irregularity.

There are many other books I want to read: Proust, the essays of Montaigne, Unshrunk (a new release by Laura Delano), Carlos Eire’s They Flew.

The culture of Substack has changed. What felt in 2021 like an unblemished pasture has slowly been replaced by the thickness of development, and I need to create a conservation easement in my mind (this is also what it means to be a conservative). The appearance of the Notes feature in April 2023 had the effect of a bulldozer rambling through a quiet field and erecting a strip mall. The arrival of Pete Buttigieg in March 2025 completed the impression of a Whole Foods having finally replaced the experimental performance venue.

I want to focus my energy on learning to work with editors. It has been great to write freely on here and to say “whatever I want,” but I want to develop the skill of collaborating and taking direction. I also want to be read in other venues.

I don’t want to hide my writing behind a paywall anymore. I have written a lot of crazy shit on here, and I haven’t erased any of it. I have noticed over time the temptation to put the really embarrassing stuff behind a paywall, and this shouldn’t be the function of a paywall.

I simply want to spend less time online.

I will continue to write on Substack and to promote my own and others’ work on this platform. I will also point to writing I have done for other publications. I am extremely grateful for all the support (including financial) that has come my way as a result of this website, and for the confidence shown in my writing by my paying subscribers. If your paying subscription is still active, you will receive a pro-rated refund in the following days (if any issues arise with this, respond to this email and let me know). All paying subscriptions will revert to free subscriptions.

Once again, thank you.

I will conclude this essay with a beautiful quote by Charles Taylor, whose latest book I am reading for a forthcoming review. The philosopher makes a statement which could apply to religious belief as well as artistic endeavor:

Any faith in far-reaching transformation is bound to encounter moments of lost intensity, when fatigue sets in, the vision weakens, and the banal facets of everyday life occlude it.

However, he also says (bold mine):

A far-reaching faith strives for deepening of the vision, which is often only possible at the cost of confusion, a loss of orientation, as the shallower insights are shed.

Finally: I will point here (as promised) to a recent review I wrote in the Washington Examiner, of Sir Diarmaid MacCulloch’s Lower Than the Angels: A History of Sex and Christianity. It is an abominable book, full of digs at the life-saving Faith by a scholar who professes to be its friend. I tried to be somewhat gallant about it in my assessment, but the fire on my tongue is still detectable. Please read it.